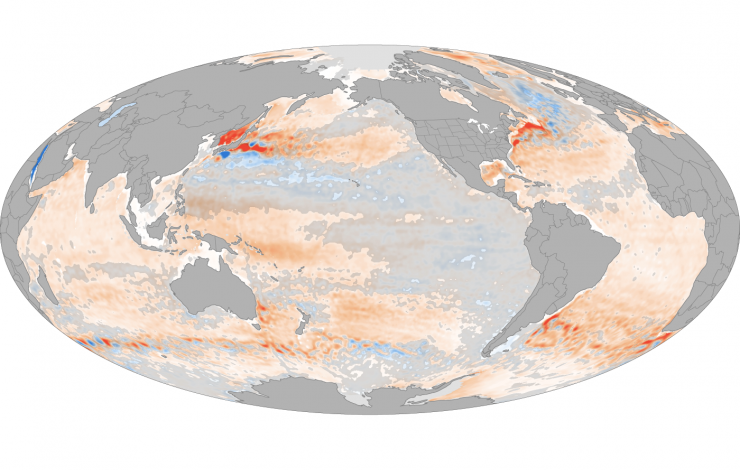

Change in heat content in the upper 2,300 feet (700 meters) of the ocean from 1993-2022. Between 1993–2022, heat content rose by up to 6 Watts per square meter in parts of the ocean (dark orange). Some areas lost heat (blue), but overall, the ocean gained more heat than it lost. The changes in areas covered with the gray shading were small relative to the range of natural variability. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data from NCEI.

Ballinger, T.J., J.E. Overland, M. Wang, J.E. Walsh, B. Brettschneider, R.L. Thoman, U.S. Bhatt, E. Hanna, I. Hanssen-Bauer, and S.-J. Kim (2023): Surface air temperature, in State of the Climate in 2022, The Arctic. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S279–S281, doi: 10.1175/10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0079.1, View online at AMS (external link).

Benestad, R., R.L. Thoman, Jr., J.L. Cohen, J.E. Overland, E. Hanna, G.W.K. Moore, M. Rantanen, G.N. Petersen, and M. Webster (2023): 2022 extreme weather and climate events [Sidebar 5.1] , in State of the Climate in 2022. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S285–S287, doi: 10.1175/10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0079.1, View online at AMS (external link).

Johnson, G.C., and R. Lumpkin (2023): Overview. In State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S152–S153, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

Johnson, G.C., J.M. Lyman, C. Atkinson, T. Boyer, L. Cheng, J. Gilson, M. Ishii, R. Locarnini, A. Mishonov, S.G. Purkey, J. Reagan, and K. Sato (2023): Ocean heat content. In State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S159–S162, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

Johnson, G.C., J. Reagan, J.M. Lyman, T. Boyer, C. Schmid, and R. Locarnini (2023): Salinity. In State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S163–S167, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

McPhaden, M.J. (2023): The 2020-22 Triple Dip La Niña, in State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans [Sidebar 3.1]. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S157–S158, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

Sharp, J. (2023): Tracking global ocean oxygen content, in State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans [Sidebar 3.2]. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S189–S190, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

Wanninkhof, R., J.A. Triñanes, P. Landschützer, R.A. Feely, and B.R. Carter (2023): Global ocean carbon cycle. In State of the Climate in 2022, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S191–S195, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

Wen, C., P.W. Stackhouse, J. Garg, P.P. Xie, L. Zhang, and M.F. Cronin (2023): Global ocean heat, freshwater, and momentum fluxes, in State of the Climate in 2022. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 104(9), S168–S172, doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0076.2, View online at AMS (external link).

The year 2022 was marked by unusual (though not unprecedented) disruptions in the climate system including a “triple-dip” La Niña nearly continuous from August 2020 through the end of 2022, extraordinary amount of precipitation over Antarctica in 2022 and the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai underwater volcano eruption in January. Greenhouse gas concentrations, global sea level and ocean heat content reached record highs in 2022, according to the 33rd annual State of the Climate report.

Surface cooling from,

triple-dip La Niña but,

seas rise, absorb heat.

PMEL researchers Greg Johnson, John Lyman, Meghan Cronin, Michael McPhaden, Richard Feely, Brendan Carter and Jonathan Sharp contributed to sections on ocean heat content, salinity, global ocean heat, freshwater, and momentum fluxes, the 2020–22 triple-dip La Niña, the global ocean carbon cycle, and global ocean oxygen content in the Global Oceans chapter. Greg Johnson continues to serve as an editor for the Global Oceans chapter along with Rick Lumpkin (NOAA AOML). Jim Overland and Muyin Wang contributed to the section on Arctic surface air temperature and extreme weather and climate events.

Notable findings from 2022 include:

- Earth’s greenhouse gas concentrations were the highest on record. Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — Earth’s major atmospheric greenhouse gases — once again reached record high concentrations in 2022. The global annual average atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration was 417.1 parts per million (ppm). This was 50% greater than the pre-industrial level, 2.4 ppm greater than the 2021 amount, and the highest measured amount in the modern observational records as well as in paleoclimatic records dating back as far as 800,000 years. The annual atmospheric methane concentration also reached a record high, which was a 165% increase compared to its pre-industrial level and an increase of about 14 parts per billion (ppb) from 2021. The annual increase of 1.3 ppb for nitrous oxide in 2022, which was similar to the high growth rates in 2020 and 2021, was higher than the average increase during 2010–2019 (1.0 ± 0.2 ppb), and suggests increased nitrous oxide emissions in recent years.

- Warming trends continued across the globe. A range of scientific analyses indicate that the annual global surface temperature was 0.45 to 0.54 of a degree F (0.25 to 0.30 of a degree C) above the 1991–2020 average. This places 2022 among the six warmest years since records began in the mid-to-late 1800s. Even though the year ranked among the six warmest years on record, the presence of La Nina in the Pacific Ocean had a cooling effect on the 2022 global temperatures in comparison to years characterized by El Nino or neutral El Nino–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions. Nonetheless, 2022 was the warmest La Nina year on record, surpassing the previous record set in 2021. With the re-emergence of El Nino in 2023, globally-averaged temperatures this year are expected to exceed those observed in 2022. All six major global temperature datasets used for analysis in the report agree that the last eight years (2015–2022) were the eighth warmest on record. The annual global mean surface temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.14 to 0.16 of a degree F (0.08 to 0.09 of a degree C) per decade since 1880, and at a rate more than twice as high since 1981.

- Ocean heat and global sea level were the highest on record. Over the past half-century, the ocean has stored more than 90% of the excess energy trapped in Earth’s system by greenhouse gases and other factors. The global ocean heat content, measured from the ocean’s surface to a depth of 2,000 meters (approximately 6,561 ft), continued to increase and reached new record highs in 2022. Global mean sea level was record high for the 11th-consecutive year, reaching about 101.2 mm (4.0 inches) above the 1993 average when satellite altimetry measurements began.

- La Nina conditions moderated sea surface temperatures. La Nina conditions in the equatorial Pacific Ocean that began in mid-2020, with a short break in 2021, continued through all of 2022. The three consecutive years of La Nina conditions — an unusual “triple-dip” — had widespread effects on the ocean and climate in 2022. The mean annual global sea-surface temperature in 2022 equaled 2018 as sixth-highest on record, but was lower than both 2019 and 2020 due in part to the long-lasting La Nina. Approximately 58% of the ocean surface experienced at least one marine heatwave in 2022, which is defined as sea-surface temperatures in the warmest 10% of all recorded data in a particular location for at least five days.

- The Arctic was warm and wet. The Arctic had its fifth-warmest year in the 123-year record. 2022 marked the ninth-consecutive year that Arctic temperature anomalies were higher than the global mean anomalies, providing more evidence of the process known as Arctic amplification, when physical processes cause the Arctic to warm more quickly than the rest of the planet. The seasonal Arctic minimum sea-ice extent, typically reached in September, was the 11th-smallest in the 43-year record. The amount of multiyear ice — ice that survives at least one summer melt season — remaining in the Arctic continued to decline. Since 2012, the Arctic has been nearly devoid of ice that is more than four years old. Annual average Arctic precipitation for 2022 was the third-highest total since 1950, and three seasons (winter, summer and autumn) ranked among the 10 wettest for their respective season.

About the report:

The international annual review of the world’s climate, led by scientists from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) and published by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Societyoffsite link (AMS), is based on contributions from more than 570 scientists in over 60 countries. It provides the most comprehensive update on Earth’s climate indicators, notable weather events and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, ice and in space.

The State of the Climate report is a peer-reviewed series published annually as a special supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. The journal makes the full report openly available. NCEI’s high-level overview report is also available online. This story was modified from the NOAA press release and Climate.gov Highlights