The Rum Creek fire burns vigorously after sunset near Merlin, Oregon on August 28, 2022. Credit: Robert Hiatt, NOAA National Weather Service

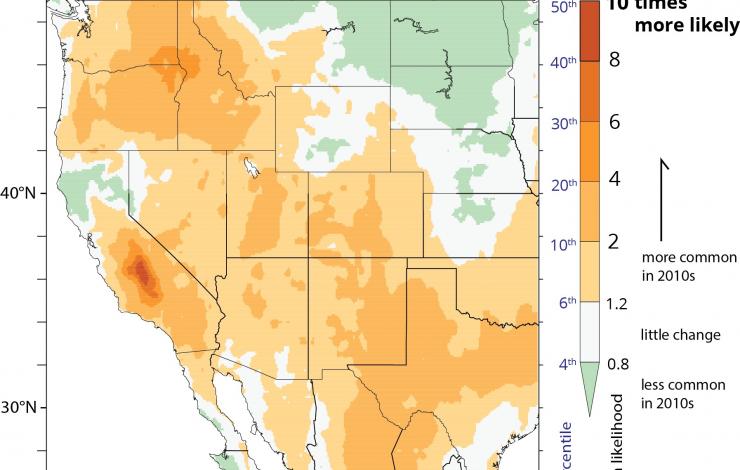

This graph shows how the frequency of nights with dry fuels predisposed to burning has increased between the 1981-2000 period and the 2011-2020 period. This has created the conditions for increased fire activity at night, a time when firefighters could once count on falling temperatures and rising humidity to give them a break. Credit: Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

For decades, firefighting crews counted on falling temperatures and rising humidity at night to dampen wildfire activity, allowing them to rest, regroup and prepare for the next day.

Over the last 20 years though, satellite measurements have confirmed a change reported in the western US by firefighters on the ground: a dramatic increase in nighttime fire activity by larger fires. Previous studies attributed the increase to warmer, drier nights, conditions that help to maintain the flammability of fuels.

New research from NOAA, the University of Washington and the U.S. Forest Service has investigated other weather conditions that influence fire behavior, the extent to which these factors have been changing over recent decades and how they may have contributed to changes in nighttime fire behavior.

"We looked for simultaneous changes in winds, atmospheric mixing and fuel moisture that might enhance nocturnal fire activity," said lead author Andy Chiodi, a University of Washington scientist working with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. "Our results show that, indeed, all the atmospheric measures that influence wildfires have changed towards supporting more intense nocturnal fire behavior."

The findings were published in the Journal of Climate.

The implication of these findings, said Chiodi, is that researchers need to better understand the interplay of each of these factors in driving increases in nocturnal fire activity, which not only complicate firefighters’ jobs, but also could jeopardize public safety.

In 2022, a study led by the US Forest Service confirmed that the amount of fire radiative power, or the amount of heat generated by burning, detected at night over the contiguous U.S. by two NASA satellites (VIIRS and MODIS) increased by approximately 50 percent during the 2003-2020 study period. That study found the change was most pronounced for the larger fires burning in drier heavy fuels that experienced more active nighttime burning.

The current study expands on Chiodi’s previous work that examined changes in night time vapor pressure deficit, which determines the rate at which woody fuels lose moisture to the air, over the western U.S. during the last 40 years. As fuels dry they become more susceptible to burning. The study found over that period that the number of dry-air nights had indeed increased.

The new paper explored not only the frequency of dry nights but also how often they were accompanied by other weather factors conducive to burning. "It’s important to know how each of these has changed to accurately interpret changes in nighttime fire behavior," Chiodi said.

Chiodi explained that typically, when the sun sets, reduced solar heating cools the surface, calms winds and turbulence, and allows for the formation of a stable layer at the surface, called the planetary boundary layer, which acts as a kind of cap. Reduced wind speeds tend to moderate fire activity. Cooler air below a lower, stable boundary layer traps humidity and smoke, which can further subdue fire behavior.

The new study found that in the 2010s, dry-fuel nights were not only more than 10 times more frequent compared to the 1980s and 1990s in some locations, fire risk was compounded by simultaneously windier and deeper boundary layers, over 81% of the Western U.S.

"So the problem is that it’s not just drying out, it’s that places that are getting drier are seeing a double or triple whammy: drier nights, more wind and a deeper atmospheric boundary layer."

The study found southern California, especially the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, are hot-spots for this trend. This region was already quite dry in terms of fuel moisture in the 1980s and 1990s. More recently, it has experienced some of the greatest increases in frequencies of dry and windy nights.

These insights not only have value for operational firefighting decisions, Chiodi said they can also help inform decisions about when conditions are appropriate for prescribed burns, which are critical for mitigating wildfire risk, especially near developed areas.

Chiodi is presently working with Forest Service colleagues to build user-friendly tools that can quickly identify safe weather windows for effective prescribed burns.