WHAT'S NEW:

Eruption Confirmed!

New lava (rumbleometer stuck in flow) SE rift zone

(posted 9/1/98)

BACKGROUND:

Technology (ROV, ships, etc.)

Other 1998 Axial cruise reports

EXPEDITION:

Science Objectives

Calendar

Today's Science News

Participant Perspective

Teacher Logbook

EDUCATION:

Curriculum

Teacher Observations

Questions/Answers from sea

MULTIMEDIA:

(video clips, animations, sounds)

Logbook

September 13, 1998

September 13, 1998

Contents:

Science Report

Daily Science Report - Sep 13

ship's location = 45 56.9N/129 59.0W

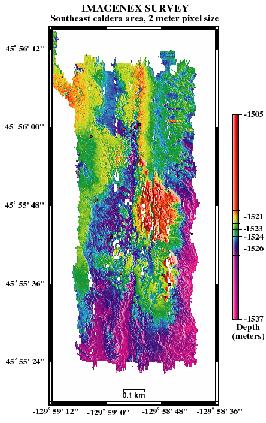

The last 3 ROPOS dives (474, 475, 476) were devoted to mapping the

northern extent of the 1998 lava flow on Axial's upper south rift zone.

It was originally intended to be just one dive but ROPOS had

to come up early twice due to vehicle problems before the mapping was

completed. In addition to the geologic traverses on the bottom and

collecting

The extensometer instruments that we recovered several dives ago,

show a 4 cm distance decrease across the measured baseline at the same

time that the earthquake swarm occurred in January 1998. This is also the

same time that the rumbleometer (the one that was recovered from the

center of the caldera) saw a subsidence of 3.2 meters! This distance

change seen by the extensometers is interpreted as due to a deflation

of the entire volcano summit as magma moved into the south rift zone.

Listing of all Science News postings

Last month, I had the opportunity to visit Rabaul in Papua New Guinea. In 1994,

the city was destroyed as two volcanoes erupted. The seismologists were able to

warn the inhabitants who were able to evacuate in time; most people have now

moved away. As I look at the new lavas on Axial Volcano, I remember the huge

fields of tubeworms we saw here last year. Then, we sat our sub in the middle

of the field and the tubeworms (called vestimentiferans) towered above us -

nearly 2 meters tall! Hundreds of thousands of worm lives were lost here. They

had no warning....and even if they did, they are attached to the rocks, and

cannot move. Why would anything choose to live in such a precarious place??

(photo below left shows "baby" tubeworms on the edge of the new lava flow)

It's the food source that brings them. You have heard from our microbiologists

describing the abundant microbes here. Chemical reactions in the vent fluid

feeds their growth and the big animals eat the bacteria. It is a very hard

place to live for many reasons: the heavy metals, the sulphide poisons, the

isolation and, not the least, eruptions and extinction. Since I have worked on

Juan de Fuca Ridge - 16 years now - nearly every animal we have found is a

species biologists have not seen before. There are over 400 new species at

vents around the world. On this ridge, we have found about 75 new species from

big worms to tiny copepods. And we have a couple more from this cruise!!

An example is the tubeworm that we first found here on Axial in 1983. The

expert in the Smithsonian named it Ridgeia piscesae - "the ridge worm of

Pisces". Pisces was the name of the Canadian submersible we were using. The

vent tubeworms belong to a group of animals you won't find often anywhere else.

They shocked biologists when first discovered....they have no mouth, no gut no

anus. Just a giant sausage in a tube with a red tuft sticking out the top.

Well that sausage turns out to be a highly evolved adaptation to vents: it is

filled with red blood and bacteria. Why bother slurping up bacteria for food

when you can just grow them inside you? The worms pick up oxygen, dissolved

sulphide, and carbon dioxide with their gills. These compounds travel in the

blood to the bacteria who use energy from the oxidation of sulphide to fix the

carbon dioxide into scrumptious sugars. The sugars pass to the worm ... how

efficient!

But what about all those dead worms buried under the lavas? Not all are gone:

we found some sticking out the edges. When we picked up some to examine (see photo right of samples being removed from ROPOS), we

found they are full of eggs and sperm - in the face of disaster, life goes on!!!

One of the projects I am doing out here is to find out how quickly the new

vents are colonized. And eight months later, it has already happened.

Different vents have different animals, which surprises me (different chemistry

maybe??). But we did find new tubeworms recruiting to the lavas. The males

fertilize the females who release tiny embryos into the water. These turn into

larvae that are carried by the currents for many days. Those babies are now

landing on the lavas. We plan to try to bring a few live tubeworms back to

Victoria where we will keep them in special conditions and see if we can make

babies there to watch how they grow.

So we have some very special animals who have evolved to live on the edge: the

constant threat of death but the continual chance for rebirth.

It is a great challenge to try to do this type of work out here. But so

rewarding. I am a Professor in

Earth/Ocean Sciences and in

Biology at

University of Victoria. Over the years, my program has evolved to work with

interdisciplinary groups such as this one. But not only is there great pleasure

in working with other scientists, the technologists and pilots of the

ROPOS

group have also taught me and my students a great deal - we delight in their

successes. And a final note: a big hug for my little girl, Arielle, who

started back to school last week; it's hard not to be there.

Listing of all Perspectives postings

September 13 - 1500 hours

It's Sunday afternoon and we have good news and bad news. After a few problems

yesterday with water alarms, ROPOS is back on the bottom taking bacterial mat

samples and surveying two more tracks along the ocean floor. Despite a one hour

delay caused by a video malfunction in the deep recesses of the hydro-lab, this

part of the dive concluded at about 1400 hours and we have begun a long run of

The bad news is that the weather report calls for some relatively nasty stuff

tomorrow and maybe beyond. We are beginning to feel the change in the ship's

motion already this afternoon. The meteorologists are predicting the 35 knots

winds that will guarantee that we'll all be "sleeping" on the cheap roller

coaster for a night or two. Still, we can't complain. There has been very

little of this kind of disturbance in our first 21 days at sea and we are still

averaging somewhere in the vicinity of 15 hours per day of dive time. That's

phenomenal.

We are still looking for questions from shore. We want to keep our scientists

in touch with what folks on shore are thinking about the work being done out

here. If you have any questions you would like to have answered, send them

through the question icon at the end of this page. One common question that has

shown up in a number of different forms is "Where are all the big animals?"

Our

biology professor from the University of Victoria addresses that question in her

science report for today. We are sending along some pictures of the big animals

that we have observed, but the truth is that the area we have been exploring is

only about one-tenth of a mile in length, and in an area of the ocean where big

animals are generally very rare due mainly to a lack of food, we just don't see

many.

We have begun a cribbage tournament among the card-playing members of the crew.

I have my first match this evening. I expect to win the whole thing, but of

course so does everyone else who is competing. The whole crew is beginning to

see the light at the end of the tunnel, and while we still have five days of

science and one day of cleaning and packing ahead of us, we are all looking

forward to a little R and R in Victoria, B.C. One week after I get home I have

to go to Washington D.C. to begin working on the second annual

National Ocean

Science Bowl. I can virtually guarantee that some of the information you find

on this website will find its way into that contest. Those of you who are

teachers at the high school level might want to start thinking about putting

together a team. Last year's contest was superb. I will post information about

the contest to this website as soon as I have reliable dates and places in hand.

If it turns out to be stormy tomorrow so that ROPOS is not able to go in the

water, I'll try to do some catch-up on things we've missed reporting along the

way, or perhaps take you on a quick tour around the ship, provided it will hold

still long enough to have its picture taken. L

Logbook of all Teacher At Sea postings

Question: What is the "bag creature"?

Answer:

A figment of overactive imaginations to some extent. The big jelly

blobs we see around the vents are not creatures at all. [When they were first

found, geologists decided that, since they weren't rock, they had to be

animal and the name stuck.] If you look at them in the lab, they are like round

lumps of Jello: transparent, often with white fuzzy growth on top.

Under the

microscope, there is no structure at all. Our microbiologists will be examining

them because we believe they are sugar wastes produced by bacteria.

So much is

coming out that they stick together and form large blobs.

All Questions/Answers from sea

Life at Sea: Participant Perspective

Verena Tunnicliffe

Professor,

University of Victoria ERUPTION ALERT!! Hi, I'm a marine biologist - my name is

Verena Tunnicliffe.

ERUPTION ALERT!! Hi, I'm a marine biologist - my name is

Verena Tunnicliffe.

(Photo show Dr. Tunnicliffe with her time-lapse camera. When deployed on the seafloor, the camera will take one photo/day of the same region to monitor change.)

Teacher At Sea Logbook

Question/Answer of the Day

Andra Bobbitt, Seal Rock Oregon

Send Your Question to NeMO

(oar.pmel.vents.webmaster@noaa.gov)

Back to Calendar