WHAT'S NEW:

Deepsea Image Galleries on Multimedia page

(posted 9/15/98)

Eruption Confirmed!

New lava (rumbleometer stuck in flow) SE rift zone

(posted 9/1/98)

BACKGROUND:

Technology (ROV, ships, etc.)

Other 1998 Axial cruise reports

EXPEDITION:

Science Objectives

Calendar

Today's Science News

Participant Perspective

Teacher Logbook

EDUCATION:

Curriculum

Teacher Observations

Questions/Answers from sea

MULTIMEDIA:

(video clips, animations, sounds)

Teacher At Sea Logbook

August 24, 25, 26, 27 28, 29, 30, September 01, 02, 03, 04 (not available), 05, 06, 07, 08, 09, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

September 19

September 19- 0900 hours

We are underway, bound for Victoria. We managed to get our last dive in late yesterday. The extensometers were positioned on the ocean floor and we had one last chance to visit the site at CASM (Canadian-American Sea Mount) where all of this began a decade and a half ago with the discovery of the first hot vents in the North Pacific. The three scientists and two Pisces pilots who were involved in that discovery are reunited on this cruise. (photo left: l-r, top: Kim Juniper, Keith Shepherd, Bob Holland, bottom: Verena Tunnicliffe, and Steve Scott) There were many changes at CASM compared to the first visit. Many dead tube worms littered the site, but other life forms were doing very well. One of the largest populations of palm worms yet discovered was seen. One of the big questions for biologists is how these vents become populated in the first place, and once they are, how does the population change over time? The ability to visit a site over a period of time will help to answer questions like these. That is the idea behind establishing a true observatory at Axial Seamount.

The truth is that while scientists have begun to answer some of the questions about the geology, chemistry, and biology of the vent systems, they may have created more questions than they answered. Despite a month of intensive observation, the scientists are asking questions, not giving answers. Not yet anyway. All of the data will have to be sifted and allowed to settle before answers will begin to appear, but along with answers that do occur will come the questions that could well form the focus of the next visit to the observatory.

Some will ask where the benefit lies in all of this for the Canadian or American tax-payer. No one has a specific ready answer for that. We do have an ore geologist on board. There is strong evidence to indicate that old ridge systems may be the source of rich ore deposits. The fact is that we all benefit in ways we cannot foresee. Freeze-dried foods and the plastic used in football helmets and the light covers on your car's turn signals came out of the American space program. What is found and what use humans make of it will be the product of those well-schooled human minds at work out here and on shore.

Today is major clean-up, pack-up and tie-down day. Video tapes are being put in order, computers torn down and boxed, and scientific equipment carefully packed away until the next voyage. I want to pick up where I left off yesterday to remind you briefly of the outstanding people I have met and the projects on which they are working. I know that some of the scientists on board have not received a fair share of coverage on the web page. Whether I failed to comprehend the complex work they are doing, or worked a different watch or in a different part of the ship, the fault is mine. The work that they are doing is just as important and as impressive as are the projects that have received more coverage. Sometimes it just came down to who was sitting across the table at dinner.

It was a real pleasure to watch scientists from Canada and United States working together, in part erasing the political differences that occasionally arise between these two great nations. ROPOS is Canadian, as are the technicians who have kept this platform operating throughout the past month. There are also three Canadian scientists on board without whom this expedition and this website would not, could not, have been as successful as they were. Kim Juniper of the University of Quebec at Montreal, with the help of his graduate students, has been responsible for much of the biological work with those samples known as "slurp samples." They have also been responsible for much of the technical advice on video records of the voyage. Dr. Juniper has taken time to read my daily reports and show me where improvements could be made. Steve Scott, a geology professor from the University of Toronto, with special expertise in mineral ores, has likewise taken time to give me basic instruction in special topics and make comments on the web page. Steve is one of a group of forward-thinking Canadians who saved ROPOS from the scrap heap a few years back. I have to offer special thanks to Verena Tunnicliffe of the University of Victoria. She not only epitomizes the scientist who is excited by the work she is doing, but she also took special pains to help me to better understand vent biology. Several times she took the questions that came in on the web and wrote concise, understandable answers. I would love to take a class from her at the University. All three of these professors are clearly teachers. All of us who have had the university experience know that this is unfortunately not always true of professors.

I also have to mention to

crew of the Ronald Brown. Everyone on board has done

their utmost to make this cruise work. The folks on deck have handled

deployment and recovery of instruments with great skill. The engineers kept the

ship running smoothly. The stewards have fed us far too well and have kept the

operation ship-shape from top to bottom. From these people I have learned a

little bit about seamanship, how a ship like the Brown operates, and how much

you have to know to be able to do any of their jobs. I have even received a few

tips about the stock market. The captain and officers of the Brown have gone

about their jobs in a way that appears practically seamless in terms of

impacting the work the scientists are doing. Their support has been essential

and appreciated. I want to make special mention of the help I received from Lt.

Alan Hilton, the ship's navigation officer.

With his knowledge of computers and

the web he not only made it easier for me to get my reports and photographs to

the web, but he also got the web pages downloaded to the ship's computers so

that participants could see how the work out here was being represented to the

rest of the world.

This has been the opportunity of a lifetime for me. I cannot conceive of a reason why I should have had the good fortune to be chosen to go to sea on a voyage of discovery this late in my career. I have thoroughly enjoyed the sea, the people, and the excitement of this voyage. I hope that those of you who read these web pages have come away with a better understanding of how and why this kind of research is important. It would be great if some student reading this makes the decision that he or she wants to put out the effort necessary to become one of the next generation of ocean explorers. It would also be great if a teacher makes a decision to contact NOAA and become a part of the Teacher-at-Sea program. It's all out here folks. All you have to do is reach out and take it.

Thank you for visiting the New Millennium Observatory (NeMO) web page. Now get back to your books and get ready for that math quiz tomorrow.

September 18

September 18 - 0900

The last working day is here. The wind is still blowing, ROPOS sits on the aft deck, and we are officially at the point of wondering if, and hoping that we can get one more dive in later today. The scientists have had such a productive cruise, it would be great if they could complete the last couple of objectives. That all depends on what the weather holds over the next twelve hours.

While I wait to see if we can deploy ROPOS, I thought it might be a good idea to

take a quick look back over this cruise and try to express once more the

admiration I have for the women and men who have spent the last 27 days

unlocking the secrets of Axial Seamount and the environment that surrounds the

vents. I have often reported on the almost "science fiction" nature of the

technology that was used. It's not just

ROPOS, although that instrument is a

wonder in and of itself. It is the various instruments that ROPOS carries to

the bottom that actually gather the data, and there is not a single device, from

water sampling bottles to the highly sophisticated

SUAVE apparatus that can be

purchased at your local electronics store or home shoppers club. These

instruments are the result of years of testing, tweaking, and re-testing. I

arrived on board just as the wave was cresting. I have seen ocean research when

it is the best it can be. The weather cooperates, and everything works. It's

been a great show. Bob Embley, chief scientist, and the whole scientific

contingent can take a deep bow.

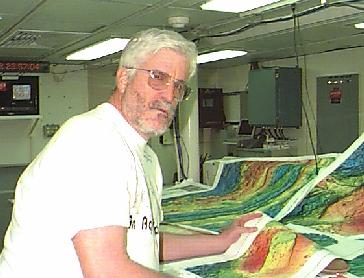

Bob Embley and Bill Chadwick (photo right) have worked long hours on improving the Imagenex maps of Axial Seamount and mapping the new lava flows by documenting the contact between new and old lava wherever it has been found.. The attempts to free the rumbleometer and the continuing efforts to deploy the extensometers also fall to these two scientists.

Air Force special delivery notwithstanding, when you come to sea you bring

supplies and tools and ingenuity, and you hope you can make it work. When

something doesn't work, you try to think of a way to make it work. The

electronics for the fluid sampler came in by special delivery, but when the pump

subsequently gave up,

Dave Butterfield and his crew figured out a way to use a

pump from another device to save the day. When you really look inside SUAVE, or

any of the other fabulous "toys" that we have on board, you see that none of

this could happen without the brilliant and dedicated minds of the scientists

who build the machines.

Gary Massoth and all the others who have spent the

better part of a decade getting SUAVE to its present state deserve the

admiration of us all. There simply is no substitute for the well-schooled human

mind.

pump from another device to save the day. When you really look inside SUAVE, or

any of the other fabulous "toys" that we have on board, you see that none of

this could happen without the brilliant and dedicated minds of the scientists

who build the machines.

Gary Massoth and all the others who have spent the

better part of a decade getting SUAVE to its present state deserve the

admiration of us all. There simply is no substitute for the well-schooled human

mind.

If, as a student, you are ever tempted to think that you can ease back because technology will take up the slack, you are sadly mistaken. I know, because I've been there, done that. A little college in Oregon is currently running one of the best advertisements I have ever seen. The thrust of the message is, "Beware of those who give you a an 'A', because they are telling you that you have arrived, that you can go home and relax. Beware of the 'A'. You have to think about it, but that is a very powerful message My students seldom understood why I was very disappointed if anyone got a 100% on one of my science tests. I simply wanted every student to understand that he/she had not achieved everything that could be achieved. There aren't any 100% marks in life. Never have been, never will be.

Given the direction most American public schools have gone the past decade, fewer and fewer students are getting this message. Everyone has to be a success. Every parent needs a bumper sticker proclaiming progeny who have been named "student of the month." And to accommodate that need we have 10 students of the month every month, and no repeats allowed. That watered down approach to education will not replace the scientists aboard this ship. The kid with a burning passion to learn, who may never be "student of the month" because she elected not to try out for cheerleader, or elected to pursue a specific goal to the detriment of the overall grade average, is the one who will be the next generation of ocean scientist. Believe it. Tomorrow I will try to hit the highlights of what has been learned in this past month. It is difficult to see how all that has happened can be distilled into a single commentary, but that's why they are paying me the big bucks. (Hmmm. Maybe for the benefit of any NSF readers out there I should speak the truth. My work out here has been as a volunteer. The truth is, I'd have paid for the opportunity.)

September 17

September 17 - 1100 hours

If there was any doubt that fall is just around the corner is was dispelled last night.. Those squalls that blew the ship off station yesterday turned into winds that peaked over 30 knots, and the confused sea-state made it impossible to get ROPOS back in the water. It also made sleeping in an upper bunk in the forward part of the ship a hit-and-miss affair. ROPOS is still on the aft deck.

Bob Embley and the ROPOS technicians are meeting out there trying to decide whether or not to try for a launch. We have apparently reached the center of this low pressure and, like the eye of a hurricane, things have temporarily calmed down. Of course as we come back out the other side we can expect increasing winds, but from the other direction. That may actually help to knock down some of the seas that are keeping ROPOS on the deck.

There are two dangers in launching ROPOS in marginal conditions. Of course the first is that with the ship lurching back and forth there is always the chance of slamming the sub against the ship. The second danger comes from what is know as a "snap load". This is the tension that is applied to the tether when the cage is suddenly pulled up and down violently by the action of the ship. It is usually during the extreme tension of a snap load that something gets separated in the tether. This could potentially lead to anything from another major retermination to loss of the sub. No one wants to take a chance on either of those. A full retermination would probably end the expedition right here since there would be little or no time left after repairs.

At the very least scientists want the extensometers in place and other bacteria traps and temperature probes back on the ship. So for now we watch the weather computer screens and wait for an opening. I go on watch at 1200 hours. It will either be four hours of thumb-twiddling, or a hectic race to beat the weather. More later.

2030 hrs

We have been high and dry all day. The barometer has dropped, winds have been steady at better than ten knots and the pilots don't like the look of the current swell, so we are in a holding pattern, hoping to get in at least one more dive before we break camp. Regardless of weather or work undone, we depart for Victoria at 0400 hours on Saturday morning, so if the last dives happen it will be later tonight and again tomorrow.

There is not much else to report tonight. The scientists are beginning to work on their summaries for the cruise log that will be published soon. Their homework assignment, and mine, is to have the summary written and submitted to the chief scientist before we land in Victoria. Other than that the big news on board is that the cribbage tournament was won by someone who spent a good deal of his freshman year at the University of Washington playing cards when he should have been studying. That would be yours truly.

September 16

September 16 - 0900 hours

And there, firmly banded to the right arm of ROPOS is a potato. A potato?? Yes,

complete with a Mr. Potato-Head face painted on. And why, you ask, is there a

potato strapped to ROPOS this morning. We are sampling high temperature vents

this morning, and high temperature combined with high pressure equals quick

cooking. This is the principal behind every pressure cooker. Under pressure

the water reaches a higher temperature without boiling and so food cooks faster.

Mr. Potato-Head is being sent to the cooking pot 1550 meters below the surface

of the Pacific. I've got to say, scientists have just a bit of weird on them.

the water reaches a higher temperature without boiling and so food cooks faster.

Mr. Potato-Head is being sent to the cooking pot 1550 meters below the surface

of the Pacific. I've got to say, scientists have just a bit of weird on them.

ROPOS has been on the bottom all night, and despite a couple of holes in the filter system, samples are being collected from a number of very hot vents. The chemists are concerned that the filter problems will invalidate their data for some of the samples, but some of the information will be useful, and their problem is now to determine which data are useful and which must be disregarded. It's the same problem you have faced in science class when the teacher says, "How confident are you about those results?" That's when you know you are going to have to do something over again!.

1400 hours

ROPOS has completed the work on the bottom and will be doing Imagenex lines for the next few hours before returning to the ship with the latest treasure trove of bottom samples. The scientists are beginning to talk about everyone having their work done. We have to replace the set of five extensometers along the northern rift zone. That will happen over night tonight. The refurbished extensometers will be loaded into the elevator and lowered to the ocean floor. Then ROPOS will take them one at a time and place them in positions where they have the necessary line-of-sight to their neighbors.

We caught some 20 knot winds in the last hour and were blown off station a

couple of times. Once ROPOS had to make a quick ascent to the cage since we

were drifting and within about 20 meters of the caldera wall. Caldera walls and

ROV's don't get along real well unless the meeting is planned. It took about

twenty minutes to put the ship back on station and then the last samples were

grabbed.

Some of you have undoubtedly figured out the head mystery. Imagine that you had

a cube of styrofoam exactly 1 inch on each side. If you were to step on that

cube and put your full weight on it, what would happen? Obviously it would be

crushed. If you weigh 140 pounds, you have just applied 140 pounds per square

inch to the styrofoam and it has collapsed. Now imagine that the pressure is

applied equally from all sides instead of just on the upper surface. Now the

styrofoam collapses equally in all directions. Instead of just being flattened,

it shrinks while maintaining roughly the shape of a cube. The ocean, at the

depths we are working, applies over one ton of pressure to each square inch of

the styrofoam head, and the head simply collapses. Since the air has been

forced out of the styrofoam, the head does not expand again as it is returned to

the surface. (photo above left)

One interesting thing that I did not notice when I photographed the heads was the calendar on the wall behind them. (photo right) Obviously the folks in the microbiology lab have some sort of countdown going on. It reminds me a lot of the calendar I kept at the end of last year when I knew that retirement was 10, 9, 8, 7. . .well, you get the idea. We are less than three days from firing up the engines and steaming for Victoria. There is plenty of work to do between now and then, but thoughts are definitely turning toward dry land.

We can't land until the cribbage tournament ends. Stay tuned to find out what member of our group wasted way too much of his or her youth playing cards.

September 15

September 15- 0900 hours

Score- Lava flow 1, Scientists 0

You can read the details in the daily science report (see 9/14 Science News), but the short form is that 2200 pounds of pull from the ship's winch could not break the rumbleometer loose from the lava flow in which it was trapped. With that amount of tension on the line, the weak link in the cable snapped. Subsequent inspection with the ROPOS showed that the rumbleometer had not budged. The camera cannot see in under the rumbleometer, but it seems like a good bet that lava may be covering the railroad wheel anchor, and may even have sealed the release mechanism in solid rock. While there are some other possibilities for freeing the instrument, it is unlikely that another attempt will be made on this voyage.

Here's something for you to think about. Send us a suggestion for how we could free the rumbleometer from the seafloor. Remember that we want to release it without destroying the data it has collected. Dynamite is out of the question. It may help you to look back at the picture of the stuck rumbleometer, but someone out there probably has a real good idea that hasn't been thought of out here. The scientists would like to have a few new ideas about now. Maybe you'll be famous. . .at least with the crew of the R/V Brown.

We knew things were going too well to be true. Over the past three days we have had a variety of small things and large things go wrong with the ROPOS or the instruments it carries. After a successful retermination yesterday, ROPOS was back in the water at about 1700, but back out again a few hours later when the usually reliable SUAVE developed a problem and had to be brought back to the ship. It was a quick turn-around and this morning ROPOS is back on the seafloor working to complete the final goals of this expedition. Time is really getting short. Every scientist would like to get just a few more samples or an extra set of data points, and who can blame them. For most it will be at least another year before they can return to the observatory. The weather has cooperated. Our big gale turned out to be maximum winds of 16 knots, and this morning I can hardly feel the ship moving.

2000 hours

Great day today!! Fabulous tube worm fields, some of the largest I have seen anywhere on the expedition. We worked right along the edge or the new lava flow. The point where new lava meets the old ocean floor is called the contact. We have spent a considerable amount of time mapping the edges of this flow and looking at the effects it has had on the ocean floor next to it. Today we found a tube worm "barbecue", a spot where a colony of tube worms was partially covered and of course killed by the hot lava. We also found and sampled what Dr. Tunnicliffe and extremely important population of tube worms growing on top of the new flow. Since this lava is only about seven months old, the biologists will have a much clearer picture of the growth rates of both individuals and communities of tube worms.

SUAVE is working fine again and the fluid sampling around vents proceeds at an

unprecedented pace. ROPOS made a scheduled return to the ship this afternoon

and is currently being fitted with the instruments that will be used on the dive

later this evening. The goals tonight are to do some sampling of high

temperature vents at Ashes and then to investigate some tantalizing hints of

perhaps more unexplored vent fields south of the previous dive areas.

I haven't lost track of the head question. I don't want to put the answer up too quickly. Look for a photograph and an explanation tomorrow. Here's a couple of small hints. First, other heads will meet a similar fate in the near future. Second, it has nothing to do with the high powered microwave ovens found aboard the Brown. Those are used to burn bags of popcorn. It's a long story, and for Julia's sake I won't go into details here. At least we didn't have to abandon ship! (photo left shows a Safety Drill)

September 14

September 14 - 0900 hours

Despite dire predictions the weather remains calm and sunny this morning. The

seas are not as large as they were yesterday. That is a pleasant surprise.

There is, however, a fly in the ointment. The "Big R" is upon us, or at least a

mild version of the "BIG R" Retermination. The tether that connects ROPOS to

the ship has developed problems that require the technicians to reconnect

(reterminate) each of the wires that power the system. Fortunately this does

not include the data-transmitting fiber optic system. If the fiber optics are

damaged the retermination can take in excess of 24 hours. This project which

will include testing of the sub's systems before re-deployment, will cause

approximately a six hour delay. The science team met Sunday evening to rough

out the plans for the rest of our dive time. This is done to be sure that a

maximum of work is completed and that every scientist gets input as to which

projects are most significant. In addition, dives can be planned to maximize

data retrieval, sample collection, and deployment of equipment during the last

week at sea. The problems with ROPOS will mean another meeting after lunch

today to adjust those remaining dives.

There are many things the scientists would like to do before Friday. Dr. Tunnicliffe wants to place a camera system along side one of the biologically active vent sites. The camera is programmed to take one picture each day for a year. The camera sled will be retrieved next year, and when the film is developed she will have a "time-lapse" picture of the growth of organisms and changes in the populations around the vent. (photo left) The geologists are intent on retrieving the data from the rumbleometer that appears to be stuck in the new lava flow. A new anchor has been attached to the rumbleometer. On our next dive a cable with a weak link will be attached from the ROPOS cage to the rumbleometer. With ROPOS standing off at a safe distance, the cage will be used to pull the instrument free of the sea floor. If it is stuck too tight the weak link will separate and the attempt will be abandoned. If the rumbleometer breaks loose and begins to rise toward the surface, it will be held by the new anchor. This will prevent it from colliding with and perhaps damaging the cage. Later, with the cage out of harm's way, ROPOS sill cut the tether and allow the rumbleometer to float to the surface where it can be recovered.

Additional goals for the remaining dives include deployment of a chemical sampler called an "osmosampler" that will remain on the ocean floor to collect data until a later cruise recovers it. Pursuing a better understanding of vent chemistry, SUAVE will be sampling along east to west transits of the vent region. A site will be selected for re-deploying the extensometers. The data has been downloaded from these instruments, They have been cleaned, greased, and supplied with at least a year's worth of new batteries. They will also be left behind on the ocean floor.

| I want to finish today's report with something of a mystery. Several of the college students brought styrofoam heads aboard the ship, and for the first couple of weeks, spent some spare time decorating them. (See "Before" photo) This "Before" picture shows the decorated heads sitting on the counter next to the incubator in the biology lab. The "After" picture shows the same heads after. . .after what? That is the mystery. What do you think caused the change in the heads? The answer later this week. |

|

September 13

September 13 - 1500 hours

It's Sunday afternoon and we have good news and bad news. After a few problems yesterday with water alarms, ROPOS is back on the bottom taking bacterial mat samples and surveying two more tracks along the ocean floor. Despite a one hour delay caused by a video malfunction in the deep recesses of the hydro-lab, this part of the dive concluded at about 1400 hours and we have begun a long run of Imagenex work. The schedule calls for 12 hours of working Imagenex lines as the scientists try to get a more accurate picture of the sea floor surrounding the vent field. One of our improving maps of this area has been sent to land and is available on above on today's (9/13) site. That's the good news.

The bad news is that the weather report calls for some relatively nasty stuff tomorrow and maybe beyond. We are beginning to feel the change in the ship's motion already this afternoon. The meteorologists are predicting the 35 knots winds that will guarantee that we'll all be "sleeping" on the cheap roller coaster for a night or two. Still, we can't complain. There has been very little of this kind of disturbance in our first 21 days at sea and we are still averaging somewhere in the vicinity of 15 hours per day of dive time. That's phenomenal.

We are still looking for questions from shore. We want to keep our scientists in touch with what folks on shore are thinking about the work being done out here. If you have any questions you would like to have answered, send them through the question icon at the end of this page. One common question that has shown up in a number of different forms is "Where are all the big animals?"Our biology professor from the University of Victoria addresses that question in her science report for today. We are sending along some pictures of the big animals that we have observed, but the truth is that the area we have been exploring is only about one-tenth of a mile in length, and in an area of the ocean where big animals are generally very rare due mainly to a lack of food, we just don't see many.

We have begun a cribbage tournament among the card-playing members of the crew. I have my first match this evening. I expect to win the whole thing, but of course so does everyone else who is competing. The whole crew is beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel, and while we still have five days of science and one day of cleaning and packing ahead of us, we are all looking forward to a little R and R in Victoria, B.C. One week after I get home I have to go to Washington D.C. to begin working on the second annual National Ocean Science Bowl. I can virtually guarantee that some of the information you find on this website will find its way into that contest. Those of you who are teachers at the high school level might want to start thinking about putting together a team. Last year's contest was superb. I will post information about the contest to this website as soon as I have reliable dates and places in hand.

If it turns out to be stormy tomorrow so that ROPOS is not able to go in the water, I'll try to do some catch-up on things we've missed reporting along the way, or perhaps take you on a quick tour around the ship, provided it will hold still long enough to have its picture taken. L

September 12

September 12 - 0900 hoursI found my way out on deck yesterday and was amazed to find that even out here the air is beginning to smell and feel like fall. Daily temperature swings are much smaller over the sea than over the land, and the humidity is always high, but the seasons seem to have much the same feel that they do on land. Maybe it's the fact that the sun is showing up notably later each morning and dipping back into the sea earlier in the evening. The changing season will also bring changes to existing weather patterns. Shortly this will not be the pleasant, relatively calm environment in which we have been working for the past three weeks. Everyone on board agrees that this has been an incredible expedition, both in terms of weather and the performance of the scientific gear on board. Those who go to sea far more often than I assure me that this is not the norm.

I went through the labs yesterday in an attempt to catch the scientists at work

on the latest treasures brought up by ROPOS. I have seen in my teaching that it

is often the biology of the sea that first attracts young students to the ocean.

The idea of becoming a marine biologist enters into the heads of many young

people well before they find out just how much work that career is going to

demand. However, in walking through the labs on the ship, I see that same kind

of enthusiasm displayed by the folks who have paid their dues and become working

marine biologists. They are genuinely and openly excited about what they are

doing. They want to share their new discoveries. That's not to say that other

disciplines aren't enthusiastic, but they tend to show their enthusiasm in a

different way. Actually it's no wonder, in this environment, that the

biologists become excited. Yesterday alone they found at least one, and

probably two new species of scale worms. Of course a thorough search of the

literature will be required before the claim of a new species will be

substantiated, but in an environment that has been little studied, most of what

appear to be new species turn out to be just that. One of the new scale worms

is considerably larger than any we have seen earlier in the voyage. These worms

were between 4 and 5 centimeters in length. (see photo above right)

I went through the labs yesterday in an attempt to catch the scientists at work

on the latest treasures brought up by ROPOS. I have seen in my teaching that it

is often the biology of the sea that first attracts young students to the ocean.

The idea of becoming a marine biologist enters into the heads of many young

people well before they find out just how much work that career is going to

demand. However, in walking through the labs on the ship, I see that same kind

of enthusiasm displayed by the folks who have paid their dues and become working

marine biologists. They are genuinely and openly excited about what they are

doing. They want to share their new discoveries. That's not to say that other

disciplines aren't enthusiastic, but they tend to show their enthusiasm in a

different way. Actually it's no wonder, in this environment, that the

biologists become excited. Yesterday alone they found at least one, and

probably two new species of scale worms. Of course a thorough search of the

literature will be required before the claim of a new species will be

substantiated, but in an environment that has been little studied, most of what

appear to be new species turn out to be just that. One of the new scale worms

is considerably larger than any we have seen earlier in the voyage. These worms

were between 4 and 5 centimeters in length. (see photo above right)

The microbiologists continue to inject sample of vent waters into air tight test tubes filled with different growth media. (photo left) The tubes are left for several hours to several days to see what kind of organisms will grow. When the tube turns cloudy it is a sure sign of rapid bacterial growth. In a cloudy liquid there may be upwards of 10,000.000 bacteria in each milliliter of solution,

Biology may be exciting, but in our hearts we know that Rocks Rule! Over at the

geology workstation,

John Chadwick uses tweezers to pick pieces of crushed ocean

floor from the wax plugs that are a part of our rock coring system. The huge

chunk of ocean floor that was caught in the wire was unusual to say the least.

Most of what we will know of the geochemistry of these young basalt lavas will

come from pieces not much bigger than a sand grain. (photo right)

John Chadwick uses tweezers to pick pieces of crushed ocean

floor from the wax plugs that are a part of our rock coring system. The huge

chunk of ocean floor that was caught in the wire was unusual to say the least.

Most of what we will know of the geochemistry of these young basalt lavas will

come from pieces not much bigger than a sand grain. (photo right)

Testing of vent fluids continues in the chemistry area. Samples are sealed in

plastic or mylar bags and transferred using a large syringe. This is to keep

samples from exchanging gases with the atmosphere. Either absorbing a gas like

oxygen from the atmosphere or giving up a gas like methane to the atmosphere

would contaminate the sample.

Given the many tests that

must be performed on each sample, only small quantities of seawater are allotted

to each test. Hundreds of test tubes and small bottles are carefully filled,

labeled, treated if necessary, and stored for later analysis. (photo left)

Given the many tests that

must be performed on each sample, only small quantities of seawater are allotted

to each test. Hundreds of test tubes and small bottles are carefully filled,

labeled, treated if necessary, and stored for later analysis. (photo left)

As this final week of our voyage winds down we are going to be asking the scientists to try to summarize what we have accomplished. It is the nature of science that one not jump to conclusions. It is better to let things settle out a bit before trying to see the big picture, so we won't be looking for any Earth-shaking announcements. NeMO, the New Millennium Observatory, is just that. It is an observatory. Scientists will come here many times to look again at the same place. Time will change what is observed. Eventually they will come to understand the place.

September 11

September 11 - 1000 hours

There has been a request to hear what people do on board ship when they are not doing oceanography. As I was thinking about how to answer that question I realized that I had not stepped out on to the deck and looked at the ocean or breathed fresh air in about 48 hours. This job is like most jobs. You end up wondering where the time went. The big difference out here is that your world is only 275 feet long and 50 feet wide and is shared by 58 other humanoid biological units. As I indicated in a previous posting, people are up and working 24 hours a day. As I write this, about one-third of the crew and science staff are asleep. Very few of us get to maintain anything close to a normal wake/sleep cycle. For the scientists, waking and sleeping are dictated by ROPOS. If the sub is down there are jobs that have to be done to keep it working properly and there are jobs that make sure that everything we see is documented in quadruplicate. If the sub is up, there are samples for virtually everyone on board. With two or three hours of sleep, scientists come to the lab to process fresh samples. The hours just after ROPOS comes to the surface are among the busiest of the day.

With that kind of work schedule, people take their recreation where and when they can. Often it is just a quick catnap in a chair. Even with all the people on board it is surprisingly easy to find solitude. A lot of books get read during a voyage like this one. I am currently reading Sherman Alexie's Reservation Blues, and Tom Clancy's Politika simultaneously. I never like to read just one book at a time.

Another place you can generally find solitude is in the ship's workout room. I was surprised to find Lifecycles, a rowing machine, weight benches and a variety of other exercise equipment in a small room deep inside the hull of the ship. Most people find time to work out two or three times a week. The ship also has a small library. There is a year's worth of paperback novels waiting for anyone who forgot to bring reading material. With something like 50 computers on board, you can believe that there is a wide variety of computer games for those addicted to such pursuits. We have everything from solitaire to bloody shoot-'em-ups.

There are also shared forms of recreation aboard. One of the most popular is the movies. We have literally hundreds of movies on board. Regular showtimes are at 1730 and 2000 hours, but other movies are run any time of the day or night. I generally see about three movies a year. I've seen about three year's worth already, and I have a week to go. There are also pickup card games at irregular intervals. Cribbage, hearts and spades are the most popular games. I got into a good hearts game with a bunch of graduate students two nights ago.20 There is an old saying something to the effect of, "Old age and treachery will defeat youth and exuberance every time." It's true, although playing hearts at 0100 hours tends to put the emphasis on the "old age."

For sports enthusiasts, we get Armed Forces Radio beamed to the ship. There is generally at least one baseball game or football game each day. I actually got to listen to much of the beloved Washington Huskies in their opening game. I gave it up with two minutes to go in the game when the Dawgs let ASU score on a 4th and 8 desperation pass. It's going to be a looooooong season.

One thing none of us has to worry about out here is whether or not we will be well fed. There are three meals served each day on a regular schedule. And snacks are available at all hours. The menus have been varied and outstanding. Some of our group are vegetarians. They find a variety of pastas, salads, fruits and desserts to keep them satisfied. The omnivores among us have also come away from the table satisfied. As examples, we have been served lobster three times, had a Mongolian barbecue, and had deep dish lasagna. There are invariably several choices of main dish. The other night I came to dinner, unfortunately not very hungry. It was "surf and turf" night. Loads of huge sauted prawns and a T-bone steak grilled to individual order. I passed on the steak, but the prawns were outstanding. The head steward is the oldest staff member on board. At 62, he has had years of experience preparing meals at sea, and the experience shows.

As you can see, it's not all work out here. Still for most folks, recreation comes in small doses. My colleague, Susan Merle, just told me she has read no books and seen no movies since coming aboard. The majority of her recreation has been three games of cribbage. I was the opponent for those three games. Old age and deceit took a severe beating that evening.

Tomorrow I will make a quick visit to labs for an update on what we have accomplished. ROPOS will go back in the water later today. Several hours of Imagenex mapping are planned, as well as collection of samples at some additional vent sites. Early in the dive scientists will be taking step one in an effort to recover the trapped rumbleometer. Stay tuned for the continuing saga of the quest for data recovery.

September 10

September 11 - 1000 hours

There has been a request to hear what people do on board ship when they are not doing oceanography. As I was thinking about how to answer that question I realized that I had not stepped out on to the deck and looked at the ocean or breathed fresh air in about 48 hours. This job is like most jobs. You end up wondering where the time went. The big difference out here is that your world is only 275 feet long and 50 feet wide and is shared by 58 other humanoid biological units. As I indicated in a previous posting, people are up and working 24 hours a day. As I write this, about one-third of the crew and science staff are asleep. Very few of us get to maintain anything close to a normal wake/sleep cycle. For the scientists, waking and sleeping are dictated by ROPOS. If the sub is down there are jobs that have to be done to keep it working properly and there are jobs that make sure that everything we see is documented in quadruplicate. If the sub is up, there are samples for virtually everyone on board. With two or three hours of sleep, scientists come to the lab to process fresh samples. The hours just after ROPOS comes to the surface are among the busiest of the day.

With that kind of work schedule, people take their recreation where and when they can. Often it is just a quick catnap in a chair. Even with all the people on board it is surprisingly easy to find solitude. A lot of books get read during a voyage like this one. I am currently reading Sherman Alexie's Reservation Blues, and Tom Clancy's Politika simultaneously. I never like to read just one book at a time.

Another place you can generally find solitude is in the ship's workout room. I was surprised to find Lifecycles, a rowing machine, weight benches and a variety of other exercise equipment in a small room deep inside the hull of the ship. Most people find time to work out two or three times a week. The ship also has a small library. There is a year's worth of paperback novels waiting for anyone who forgot to bring reading material. With something like 50 computers on board, you can believe that there is a wide variety of computer games for those addicted to such pursuits. We have everything from solitaire to bloody shoot-'em-ups.

There are also shared forms of recreation aboard. One of the most popular is the movies. We have literally hundreds of movies on board. Regular showtimes are at 1730 and 2000 hours, but other movies are run any time of the day or night. I generally see about three movies a year. I've seen about three year's worth already, and I have a week to go. There are also pickup card games at irregular intervals. Cribbage, hearts and spades are the most popular games. I got into a good hearts game with a bunch of graduate students two nights ago.20 There is an old saying something to the effect of, "Old age and treachery will defeat youth and exuberance every time." It's true, although playing hearts at 0100 hours tends to put the emphasis on the "old age."

For sports enthusiasts, we get Armed Forces Radio beamed to the ship. There is generally at least one baseball game or football game each day. I actually got to listen to much of the beloved Washington Huskies in their opening game. I gave it up with two minutes to go in the game when the Dawgs let ASU score on a 4th and 8 desperation pass. It's going to be a looooooong season.

One thing none of us has to worry about out here is whether or not we will be well fed. There are three meals served each day on a regular schedule. And snacks are available at all hours. The menus have been varied and outstanding. Some of our group are vegetarians. They find a variety of pastas, salads, fruits and desserts to keep them satisfied. The omnivores among us have also come away from the table satisfied. As examples, we have been served lobster three times, had a Mongolian barbecue, and had deep dish lasagna. There are invariably several choices of main dish. The other night I came to dinner, unfortunately not very hungry. It was "surf and turf" night. Loads of huge sauted prawns and a T-bone steak grilled to individual order. I passed on the steak, but the prawns were outstanding. The head steward is the oldest staff member on board. At 62, he has had years of experience preparing meals at sea, and the experience shows.

As you can see, it's not all work out here. Still for most folks, recreation comes in small doses. My colleague, Susan Merle, just told me she has read no books and seen no movies since coming aboard. The majority of her recreation has been three games of cribbage. I was the opponent for those three games. Old age and deceit took a severe beating that evening.

Tomorrow I will make a quick visit to labs for an update on what we have accomplished. ROPOS will go back in the water later today. Several hours of Imagenex mapping are planned, as well as collection of samples at some additional vent sites. Early in the dive scientists will be taking step one in an effort to recover the trapped rumbleometer. Stay tuned for the continuing saga of the quest for data recovery.

September 10

September 10

Although ROPOS has been busy all day, I had the opportunity to interview one of our scientists on board. What follows is the result of that interview.

Conversation with a Scientist

Lee Evans is a chemist employed at Hatfield Marine Science Center for the Vents Program. His goal for this and other voyages like it is to "suck gas out of volcanic juice." Not just any gas or all gases, but those particular gases that do or may illuminate our understanding of the dynamics of mid-ocean ridges in general and Axial Seamount in particular.

Evans is particularly interested in helium. Helium is a very lightweight gas that exists in two basic forms, or isotopes. Helium-3 contains two protons and one neutron. Helium-4 contains two protons and two neutrons. Evans wants to know the ration of He-3 to He-4 in vent fluids. He wants to know how this ratio and how the total concentration of helium varies geographically from vent to vent, and temporally at any given vent.

Helium is not a particularly common element on Earth, Atoms of helium in the air migrate to the upper atmosphere and away from the ocean. So why is there helium in seawater? The answer to that question lies in what we already know. Helium is more concentrated in vent fluids than in the open sea. The vents are supplying helium to the ocean. Generally speaking the hotter vents are richer in helium because they are in closer contact with the degassing magma that is releasing helium and other gases in response to the lowered pressures near the Earth's surface.

How does helium get into the magma? Scientists believe that the interior temperature of the Earth is maintained by the decay of naturally radioactive elements like uranium. This decay, in addition to producing heat, produces atomic fragments. Sometimes, as in the decay series that leads from uranium to thorium, a portion of the decay fragments are helium atoms. Produced in the heart of the Earth, helium atoms begin a long migration that will take them through the ocean, into the atmosphere, and finally into space. Evans traps a few of them and counts them as they leave the crust and enter the ocean.

How is helium captured? Evans uses gas-tight bottles to collect his samples.

These very expensive titanium collection devices are manufactured to maintain

extreme pressure and temperature gradients. The bottles can be evacuated and

lowered into an environment with an ambient pressure of 200-300 atmospheres and

temperatures of more than 300 degrees Celsius,and no water leaks into the

bottle. Once the bottle is filled with vent fluids under high pressure, the

same system prevents the gases Evans wants to collect from leaking out of the

bottle as it is returned to the one atmosphere pressure and 10 degree Celsius at

the surface.

How the helium and other gases are separated and analyzed is a long story, but a picture of the device used to begin the process in included here. (photo right) Ultimately the isotopic ratios will be determined in laboratories on shore. The gas extracted by this equipment is sealed in glass tubes for transport to the labs.

There are some interesting ancillary benefits that derive from our knowledge of helium in vent waters. Since concentration of helium, and presumably He-3 to He-4 ratios, vary from vent to vent, helium becomes a very good tracer in the deep ocean. By tracing the movement of water masses bearing the helium signature it may be possible to learn the direction of some deep ocean circulation.While not all deep waters carry a recognizable source-specific helium signature, those that do allow a reality check for computer generated models of oceanic circulation. At the very least this allows us a clearer understanding of the processes that may be driving global climate cycles. It may seem like a big jump from counting helium atoms to understanding global climate or the structure of the Earth's interior, but that is what brings scientists like Evans to bounce around on the surface of the sea while high tech ships and high tech systems go about the business of collecting water samples leaking from some of the newest crust on Earth. Does Evans enjoy his work? He claims it pays the bills, but if you watch him go about his work you know it means more to him than he is letting on. If you would like to know more about what scientists have discovered regarding vent gases, try visiting the Vents Program's Helium Isotope Laboratory web page.

September 9

September 9 - 0900 hrsToday begins as yesterday ended with the Brown holding station over the vent area called Ashes, and the ROPOS going about the business of examining at close range the biology, chemistry, physics and geology of the sea floor. As a teacher, I always had a special appreciation for Wednesday, the "hump day" when we knew the week was half over, we were "over the hump" , and Friday wasn't far behind. I heard one of the ship's crew use that term out here yesterday. Our month at sea only has 11 days left to go. It's hard to believe that we are that close to finishing this voyage of discovery.

The Brown is "staying on station." Since oceanography became a scientific field of study there has always been the problem of knowing where your ship is with any degree of accuracy. With no landmarks of any kind, it's hard to know where you are. We have come a long way from the chronometer and the sextant, although any competent sailor still carries and knows how to use these venerable instruments to establish his or her location at sea. Modern satellite technology and our Global Positioning System (GPS) have simplified the navigation problem by allowing us at any instant to determine our exact location on the surface of the Earth.

The kind of research that NeMO scientists are doing requires that we not only know where we are and be able to find our way back, but once we find our target, the ship has to be able to maintain it's position for, in our case, hours at a time. In some meteorological studies, the Brown may have to maintain a station for a month or more. Given the waves, winds, and currents that constantly act to move the 3,250 ton Brown every which way, how does the ship maintain a fixed position? If the scientists want to move the ship southwest by west at one quarter knot, how does the crew make that happen? The answer is computers. I was given a great tour of the ship's inner workings today, from the generators that supply the "clean" power for our personal computers to the evaporators that keep us supplied with plenty of fresh water. Again we've come a long way from the days when buckets were set out to collect rain for drinking water.

The heart of the position control system on the Brown is a set of three thrusters, two aft and one in the bow. By changing the speed of the motor driven prop and the direction of the thruster, the ship can be gently nudged in any direction to counterbalance the forces of nature. The three thrusters are constantly operating under the direction of a computer driven navigational system that relies on the GPS readings received on the bridge. This is a job no human being could possibly do. The positioning of the thrusters and the speed of their motors changes on a second by second basis in order to prevent the ship from pulling ROPOS away from its position along the ocean floor. Of course there are limits to any system. In winds above 20 knots it becomes extremely difficult for the system to maintain the exact position required. For this reason, in addition to the difficulty in moving ROPOS onto and off the deck in big waves, scientists generally choose not to put the submarine out in those kinds of conditions.

1600 hours

ROPOS had a very long dive last night and today. Chemical and geological samples were collected and the dive ended early this afternoon when nearly every system on board the ROV had developed major or minor problems. As of 1600 hours the ROPOS is on the aft deck being prepared for dive number 473 later tonight or early tomorrow. In the biology lab everything from worms to limpets to pycnogonids (see photo) have been identified, counted and catalogued. The microbiologists have cultured the thermophilic (heat-loving) bacteria on a variety of media, and report that there are many thriving colonies appearing. They may even have found some new critters, but I suspect that DNA tests will have to conducted back on land to prove or disprove this claim.

We are down to ten days left with lots of work yet to be done. Stay tuned.

September 8

September 8 - 0800 hours

Uh-oh! The teacher made a mistake. It was either a case of brain lock or I was on auto-pilot several days ago when I reported that transponders signal each other with radio signals. The reason that submarines have to come to the surface to use radio communication is that radio signals don't transmit through water. Transponders actually communicate with each other using acoustic, or sound signals. Now that I have admitted to the only mistake I have ever made in my life, I am ready to explain how transponders are going to be important in the work that we are doing today.

You may remember that three days ago, just before the storm, we had

picked up

the five extensometers from the sea floor and deposited them in the elevator.

The elevator and the extensometers have been parked on the sea floor ever since,

held in place by a wheel from a railroad car. Yes, you read it right,

Old

railroad car wheels are one of the most popular items used to anchor equipment

to the sea floor.

Not only are they plenty heavy, but when they are left behind

the simply rust away. Any plankton specialist will tell you that lack of iron

in the water is the a limiting factor in the growth of single celled organisms

in the sea. So you might say that far from adding to the pollution problem in

the sea, the wheels are adding much needed nutrients.

Back to the extensometers. There has been a bit of a problem in communicating with the release mechanism that holds the elevator to the anchor. We are in the process of moving the navigation and ranging from the ROPOS cage to a device known simply as El Guapo, the handsome one. El Guapo (photo left) got its name because it is one of the ugliest pieces of equipment on board. El Guapo should allow us to transmit the release codes to the elevator, and then floats attached to the elevator will cause it to rise at a rate of about 1 meter per second, bringing it to the surface in about 45 minutes. There is a flashing strobe atop the elevator that will allow us to spot it on the surface. It was interesting to watch the ROPOS operators navigating back to the elevator with each of the extensometers. Instead of navigating with the usual bank of bright lights used on other dives, the pilot would turn off the lights and simply look for the flashing strobe which is easy to see at considerable distance in the inky blackness of the deep sea. The lights were turned back on only when it was time to deposit the extensometer into its plastic tube on the elevator.

0900 hours

Attempts to communicate with the elevator have failed. Fortunately there is a backup plan. ROPOS can dive down and grab a release cable on the elevator, manually releasing it from the bottom. This will be a quick dive for ROPOS. Just down and back. After we have recovered the elevator ROPOS will be outfitted for the next science dive.

1200 hours

ROPOS has just released the elevator from the ocean floor. We have about a one hour wait for the elevator to reach the surface. The ship is being positioned for recovery and then we are off again for another dive on Ashes. That dive will probably not begin until late this evening, so I hope to have some new information from that dive site tomorrow.

September 7

September 7 - 0800 hrs

An eventful evening and we are back in business this morning. ROPOS went back in the water early when the "weather event" was far shorter than we expected. The repaired fluid sampler was on board for the first time. There were anxious minutes when there was a power loss to the sampler and the programs that run the device were rebooted. After about 10 minutes everything came up green lights and we were able to take our first six samples of water directly from the hot vents on Ashes. While the fluid sampler can handle most hot vent water easily, it does have its limits. The operators have to be careful not to sample the hottest waters without giving the sample a chance to cool as it enters the sampler. After the six samples were gathered, a collision between the ROPOS and some underwater obstruction caused a problem with the seven-function arm, and by 2300 hours the ROPOS was back on deck for a quick repair. Keep in mind that a quick repair for ROPOS is a minimum of four hours on the deck plus an hour and a half of time in the water column. Despite this minor setback ROPOS is in the water this morning, and we are looking forward to a long a productive dive today.

1600 hrs

I've just come off my watch. During the past four hours we have returned to several of the hot vent sites to use the fluid sampler. We will not know the results of these collections until the water is brought back aboard for analysis. The fluid sampler continues to operate smoothly which is very much a relief to chemist Dave Butterfield who has struggled through some long days getting the device to work properly.

An interesting discovery today was two hot vents that were producing gas bubbles along with fluids that ranged upward to 40 degrees Celsius. Scientists in the hydrolab reported having never seen this phenomenon before. There was a lot of speculation about what the bubbles might be. The consensus at this point is that they are probably carbon dioxide. Given the tremendous pressure at this depth, it is rare to see bubbles in the environment. It is not clear what happens to these bubbles. They are intact when they leave the view of our cameras, but if they are in fact carbon dioxide the chances are that they dissolve in seawater long before they reach the surface of the ocean.

Despite the end of the strong winds, the ocean is still populated with upwards of 3 meter swells. Swells are waves that are no longer being influenced by the winds that created them. They tend to be much more regular than the waves that are being whipped up by an active wind. The interesting thing about the swells out here today is that they are running at almost exactly right angles to the heading the ship uses to hod its position over the dive site. The result has been that we have spent almost all of the day "in the trough" which means that the ship is rolling from side to side as each wave passes by. The side-to-side motion has been worse than it was during the storm. Several times today we have been picking up loose objects that slide off counter tops. Fortunately it is a very regular motion, so nobody is looking particularly green around the gills (seasick). It rained a little this morning. That is our first real rainfall of the expedition. We'll try to pass that rainfall on to the drying forests in Oregon and Washington.

School starts tomorrow for all my ex-colleagues and students at Sunset High School in Beaverton, Oregon. I'd just like to pass along this reminder: "Hi guys. I'm here, and you're not."

September 6

September 6 - 1400 hours

It has been a very quiet day on board the ship. Most of the scientists are taking advantage of the break in the dive schedule to catch up on some much needed rest. Extra movies are being shown and books are being read, or in the case of college students, studied. No one reads a Calculus book for fun! The weather is settling back sown. Winds have dropped to less than 10 knots and the barometer is rising rapidly. We expect to be putting ROPOS back into the water at about 1700 hours this afternoon.

|

Ship's Senior Survey Technician, Jonathan Shannahoff and Scientist Susan Merle (Vents), operate the bathymetric mapping system (Sea Beam) during a mapping survey. The monitor shows the swath of bathymetry data as it is collected. (photo: NOAA Vents 1998) |

Meanwhile the ship time is still expensive and so we have moved north of our previous work area and are using SeaBeam to map some areas of the ocean floor that have not previously been carefully charted. Susan Merle, who has been a huge help in getting the material for these web pages put together, is responsible for much of the navigational data that is handled through the hydrolab. She and Jonathan are pictured here working with the SeaBeam. While our Imagenex system maps a swath about 70 meters wide in great detail, the SeaBeam collects data from a swath about 5000 meters wide at a much lower resolution. While collecting SeaBeam data is very important, we hope we don't end up doing too much of it because that means either ROPOS is disabled or the weather is bad.

For those of us who are infrequent visitors to the sea there is a danger of assuming that equipment and weather always cooperate as they have on this trip. Scientists who have been here often report that actually this performance by ROPOS has been absolutely spectacular, and up until the last 24 hours the weather has been superb. For those of you who have never been to sea, let me try to explain what the weather felt like this morning. If you can imagine being in your bunk with the bunk strapped to the top of a cheap carnival roller coaster for about 12 hours you have a pretty good idea of midnight to noon today. First you feel like you are nearly weightless and floating up off your bunk as the ship drops out from under you , and seconds later you are being pushed down through the mattress as the ship rides up over the next wave. All of this is accompanied by the sound of waves striking and the anchor bumping against the hull.

The science team met just a few minutes ago to go over plans for the next dive and to rough out a plan for the remaining two weeks of the expedition. The replacement pump seems to be doing its job on the fluid sampler (this was the part delivered by the Air Force), so that will be an important part of upcoming dives. We will also be returning to Ashes and, if time allows, scouting around for a new vent area of which we are seeing tantalizing hints in the analysis of water samples from out latest CTD samples. I may not have mentioned the Conductivity-Temperature-Density (CTD) sampler, but it is one of the most common tools used for sampling water.

It is nearly time for dinner, and since neither breakfast or lunch seemed like all that good an idea, I am definitely ready. If I haven't mentioned the galley staff yet, they are to be congratulated for serving excellent meals to upwards of 60 people three times a day. They are keeping us healthy and happy!

September 5

September 5 - 0900 hours

|

Scientist Dave Buterfield examines the part delivered by the Air Force. The component will enable the water sampling instruments to function on the ROV. |

At about 0300 hours this morning ROPOS was back in the water, once again not

carrying the fluid sampler that has remained a problem for the scientists who

are working with it. The computer board that was delivered by the United States

Air Force (McChord Air Force Base, 62nd Airborne's Sonic 11) yesterday is working perfectly, but now there is a problem with one of

the pumps that moves the fluids from the vent into the containers within the

sampler. Scientists are still confident that they can get the pump working

properly and be ready for the next dive.

At about 0300 hours this morning ROPOS was back in the water, once again not

carrying the fluid sampler that has remained a problem for the scientists who

are working with it. The computer board that was delivered by the United States

Air Force (McChord Air Force Base, 62nd Airborne's Sonic 11) yesterday is working perfectly, but now there is a problem with one of

the pumps that moves the fluids from the vent into the containers within the

sampler. Scientists are still confident that they can get the pump working

properly and be ready for the next dive.

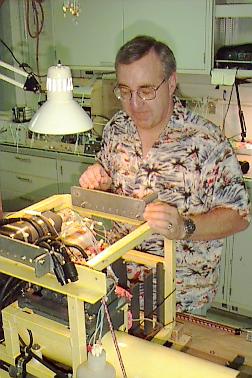

In the meantime ROPOS has been involved in retrieving a set of instruments called extensometers. These five signaling devices have been on the sea floor for the past two years. They are designed to measure the rate at which the seafloor is spreading at the Juan de Fuca Ridge. The plan calls for placing the extensometers into a device called the "elevator" that will transport the instruments to the surface. Aboard the R/V Brown scientists will transfer stored data, replace the batteries, and prepare the extensometers for the return trip to the sea floor. For these devices to work properly they must have "line-of-sight" between them. The last time they were deployed problems with the winch system meant that they were simply dropped over the side of the ship. Bill Chadwick, whom you have met in the scientist's page, tells me that they may find little if any useful data from this first experiment. This time, once the batteries are replaced, the extensometers will be placed by ROPOS in positions where we know they will have the required line-of -sight. The instruments operate on standard D-cell batteries (about a meter of them) but they only wake up for about ten minutes each day to communicate with their neighbors, so the batteries last for a couple of years.

Transducers atop each instrument "ping" their neighbors on either side and wait for the responding "ping" to come back. By very accurately measuring the time that this takes the instrument is able to determine if the distance between itself and its neighbors is changing due to movement of the seafloor. The accuracy of the entire string of five extensometers is designed to be within one centimeter of the actual distance. Since the transducers can be moved slightly by currents, there are magnetic compasses and inclinometers included in the electronics package for each instrument. Data from these devices allow the computers to adjust readings back to the zero point for the transducer. Of course the temperature of the surrounding water must be measured since temperature affects the speed of sound through water. When all of these adjustments have been made scientists can determine if and by how much each of the extensometers has moved relative to its neighbors. By such careful, accurate, and repeated measurements are the movements of the ocean floors determined.

Chief scientist, Bob Embley, reports that the ballpark average spreading rate on this portion of the ridge is on the order of 5 cm/yr. The rate is rather "herky-jerky" near the ridge, driven by magma movements within the earth. Well away from the ridge the movement becomes much more consistent since the irregular movement of the ridge is absorbed by the entire plate. Of course at the other plate boundary where this ocean floor dives abruptly under the western edge of North America, things become extremely jerky again. Locked up against the edge of the continents, the plate builds up strain over perhaps hundreds of years before releasing the strain in a major earthquake. Some scientists say the British Columbia, Washington and Oregon could experience as much as an 8.5 or 9.0 earthquake sometime in the next century.

Have you checked your earthquake insurance recently? Have you prepared your emergency survival kit? You can get a free booklet from the Red Cross that will explain preparations you should be making.

ROPOS continues this afternoon to make sonar surveys of the ocean floor. There is nothing to see on the video screens since ROPOS flies about 30 meters above the seafloor for these surveys. We are all going about getting jobs finished and loose items packed away before the weather gets here. Tomorrow may be a short and bouncy report. Stay tuned.

September 3

September 3- 0800 hours

|

Scientists swarm to ROPOS as soon as it comes back aboard to recover their samples. (photo: ROPOS NeMO 1998) |

Overnight scientists found good evidence of yet another new lava flow on the sea floor. As compelling as the evidence is, scientists are still seeking what they refer to as the "smoking gun." That would be a fresh lava flow complete with hot vents. This would establish an absolute link between the two phenomena. It seems intuitively obvious, but intuition is not proof, and scientists live on proof.

The camera that sits on the ROPOS cage has been acting up again today. Yesterday's cruise ended when the camera stopped functioning altogether. This is the camera that is used to dock ROPOS in the cage at the end of each dive. Without it the technicians must bring the cage and ROPOS close to the surface and perform the docking visually. If the camera continues to perform erratically, this dive will probably be a short one.

1400 hours

The word on board today is ROCKS!, as in "Rocks Rule!" We have samples of some

of the world's newest ocean floor (photo shows new glassy lava) aboard the R/V Brown. Glassy basalt lavas

that may be less than a year old were brought aboard in the sampling box just

before noon today. Then while running a routine rock core that usually produces

samples the size of sand grains or small pebbles, the line became entangled with

about 250 pounds of ocean floor.

The word on board today is ROCKS!, as in "Rocks Rule!" We have samples of some

of the world's newest ocean floor (photo shows new glassy lava) aboard the R/V Brown. Glassy basalt lavas

that may be less than a year old were brought aboard in the sampling box just

before noon today. Then while running a routine rock core that usually produces

samples the size of sand grains or small pebbles, the line became entangled with

about 250 pounds of ocean floor.

This piece was hauled aboard in one chunk. Geologist John Chadwick is seen in his "ultra-cool" shades displaying his treasure.

Our chief scientist will be doing a piece on these new lava flows and will include pictures taken directly from the seafloor. Check it out for some of the most spectacular geological sights we've seen out here. Basalt Background

In general, basalt lavas contain little or none of the mineral quartz. This makes basalt lava very fluid. As it pours from the tear in the Earth's crust the lava has a tendency to spread out in relatively thin sheets. Of course when it strikes the very cold seawater it cools quickly into basalt glass on its surface. The still molten rock beneath this glassy crust can continue to move, and it is this combination of flowing lavas and glassy crusts that create much of the fantastic geological structures we see near the vent areas. Among these are sheet basalts, lobate flows (pillow lavas) and basalt columns that support thin crusts over areas from which the molten lavas have drained. These thin crusts often collapse creating the cave like structures seen in some of the pictures we are taking on the seafloor.

The dark color of basalt is due to the presence of metals like iron and

magnesium in this lava. Our scientists are particularly interested in these

very young lava flows because they will be able to see how ocean floor rocks

change over time. It is interesting to learn about all of the tests that are

run on these rock samples. For instance, in one test the rocks are crushed very

fine and melted at high temperature. Scientists then look at the concentration

of the isotopes of gases like helium to give them clues about the origin of the

magmas that formed these flows. As I mentioned in an earlier posting,

scientists aboard this vessel will be looking at the concentrations of certain

rare-earth elements such as samarium and neodymium as well as the ratios of

these elements to other elements in the rocks. Their goal is to support or

refute the idea that Axial seamount is produced by a hot spot has not always

been under the Juan de Fuca Ridge. The westward motion of the Juan de Fuca

Ridge has caused it to ride over the hot spot at this point in time, and we are

seeing the results in Axial seamount. Perhaps some rock brought up by this

expedition will change that whole story. That is the nature of science.

The dark color of basalt is due to the presence of metals like iron and

magnesium in this lava. Our scientists are particularly interested in these

very young lava flows because they will be able to see how ocean floor rocks

change over time. It is interesting to learn about all of the tests that are

run on these rock samples. For instance, in one test the rocks are crushed very

fine and melted at high temperature. Scientists then look at the concentration

of the isotopes of gases like helium to give them clues about the origin of the

magmas that formed these flows. As I mentioned in an earlier posting,

scientists aboard this vessel will be looking at the concentrations of certain

rare-earth elements such as samarium and neodymium as well as the ratios of

these elements to other elements in the rocks. Their goal is to support or

refute the idea that Axial seamount is produced by a hot spot has not always

been under the Juan de Fuca Ridge. The westward motion of the Juan de Fuca

Ridge has caused it to ride over the hot spot at this point in time, and we are

seeing the results in Axial seamount. Perhaps some rock brought up by this

expedition will change that whole story. That is the nature of science.

Repairs on ROPOS are nearing completion. We will soon be heading for the black smokers in the area known as Ashes. You won't want to miss that.

September 2

September 2 - 0753 hours

Bells ringing. . ."Fire. This is not a drill. Repeat, this is not a drill. Report to your assigned station." You learn just how fast you can get out of the upper bunk. Less than one minute later, "Belay, belay. Smoke from the incinerator room. Stand down." An interesting way to start the day. You might think that with all this water around us, fire on board would be no big deal, but the idea here is to keep the water outside the ship. I remember my science teacher droning away about buoyancy or density or something like that.