Follow the Saildrone 2019

2019 Arctic Saildrone Mission

7 JAN 20 - Arctic Mission Highlighted (Saildrone Inc., January 2020)

Sailing Over the Ice Edge: The 5th annual Arctic mission, in partnership with NOAA and NASA, took a fleet of saildrones to a new frontier—the Arctic ice edge—to improve sea ice prediction and satellite algorithm development. Story can be found HERE.

19 NOV - 2019 Arctic Mission Concludes

Unalaska, AK - After 147 days gathering measurements and chasing ice, five saildrones have safely returned to the docks in Dutch Harbor. For the past five months, NOAA and partners were keenly observing real-time changes in the U.S. Arctic.

Successfully Chasing Sea Ice

This was the first year NOAA scientists and collaborators not only worked together and intentionally brought the drones as close to Arctic sea ice as possible, but also the first time observations from a mission were compared to numerical weather predictions in real time. For much of the mission, the drones purposefully followed and on occasion, though not intentionally, ran into strips of floating ice to assess changes in the Arctic energy balance during the rapid shifting of the sea ice. Chidong Zhang, oceanographer with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, led the mission focused on observations to enhance sea ice prediction. "This was a great first saildrone mission targeting sea ice. We ran into the sea ice several times, and were able to make unprecedented observations of both the ocean and atmosphere right in it.” Zhang said. These measurements revealed that surface net heat fluxes vary substantially, and that numerical predictions in the Arctic within a short range can be very good for certain variables but not for others, but their longer time predictions deviate quickly from the drone observations. The team hypothesized that gradients might be gradual and indicate when ice was nearing. But that wasn’t the case. “Unexpectedly, we found that there are much sharper gradients in sea surface temperature and salinity near sea ice than expected”.

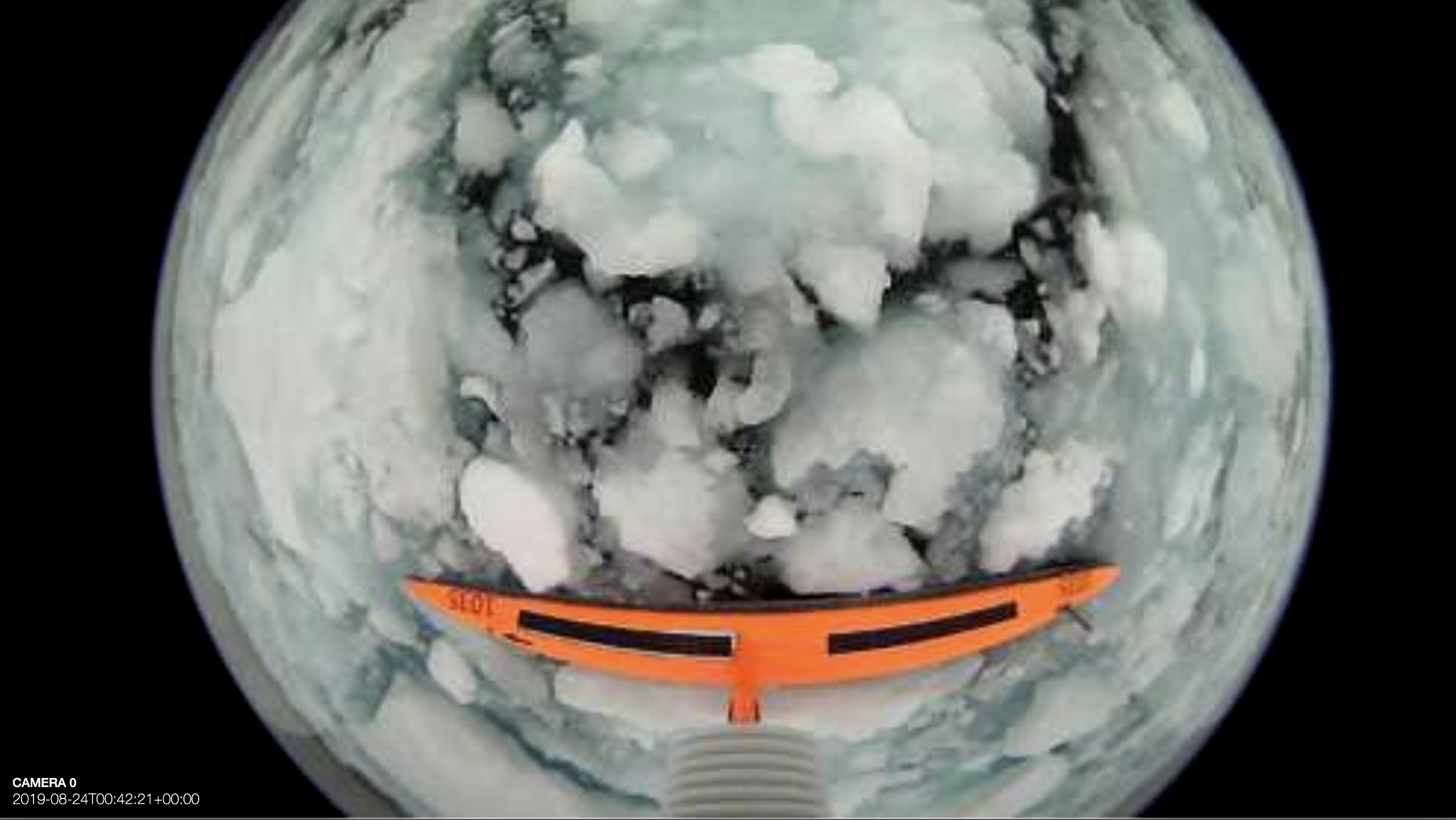

This made navigation even harder. Without a watchkeeper, limited images being sent back via satellite, and the inability to use ocean variables as a warning - the biggest challenge this season was navigation among many floating ice bands - which are highly unpredictable.

Andy Chiodi, researcher at the University of Washington’s Joint Institute for the Study of Atmosphere and Ocean and co-mission manager this year, juggled forecasts, vehicle performance and and ice to safely navigate the drones near the ice edge. “Every day was a new planning hurdle,” said Chiodi. “Each day, we would analyze a variety of ice and weather forecast information, vehicle power and solar or wind charging likelihood and compare this information with overall mission objectives and constantly changing ice distributions to decide upon weekly to hourly vehicle routes and sampling patterns”. Over the course of the mission, the team used about 15 products before settling on a few that seemed to be the most accurate. This daily routine kept the drones safe, but not without a few lessons learned. From heavy cloud cover blocking imagery of ice in the water, to many free-floating ice bands not visible to satellites and not predicted by models, or no wind and a strong current - the team quickly learned they could not rely on water temperature to let them know ice was near.

Chiodi is quick to point out that they key to success was in open and frequent communication between the large team of scientists and engineers. “The overall support of one another, sharing of lessons learned from decades of working in Arctic ice-laden waters, and co-coordination with native communities along the North Slope of Alaska, were essential to getting the science needed and drones safely home.”

Carbon in a Changing Arctic

For a month of the mission Jessica Cross, oceanographer with NOAA's PMEL, continued use of drones with specialized carbon sensors for the third year in a row, to study how the region is absorbing carbon dioxide and our understanding of ocean acidification in these critical ecosystem areas. Cross’ work focused on highly productive study sites of the Distributed Biological Observatory in the Bering and Chukchi Sea. Cross, who collaborates with NOAA's Arctic Research and Ocean Acidification Programs was also on the USCGC Healy this year during the annual rendezvous with the carbon drones.

The annual rendezvous is an important part of the saildrone mission, where we are able to compare data collected by the ship and the drone in the same place at the same time. But, it’s also an exciting day for all the scientists and crew on board. “It’s really fun to meet the Saildrone out at sea,” says Cross. “It’s like getting to wave hello to an old friend you only get to see once a year.”

During this mission, Cross used the saildrones to explore how carbon dioxide concentrations changed close to the sea ice. Because the sea ice helps stabilize the marine environment, we often find big phytoplankton blooms nearby. Cross was able to identify big ice-edge blooms near ice we saw on the Chukchi Sea shelf-- but not out in the basin, far away from land. “Land provides key nutrients that help feed phytoplankton,” Cross explained. “Instead of photosynthesis, physics runs the show out in the basin.”

A New Approach to Understanding Predator-Prey Relationships to Aid Marine Mammal and Fisheries Management

This year, one drone was dedicated to research in the Bering Sea, home to the largest walleye pollock fishery and a depleted stock of northern fur seals that aggregate on the Pribilof Islands. Alex de Robertis, a fisheries biologist and Carey Kuhn, an ecologist, both with NOAA's Alaska Fisheries Science Center, have been working together with a new method of understanding prey consumption of ecologically important species. The fisheries echosounder on the drone captures the amount of walleye pollock in the water column. To get this seal’s eye view - they tagged female fur seals, as they had previously done, but fed data from the tag to the drone to follow a particular fur seal. A second tag, this time a camera, recorded the female fur seal when she was actively hunting for a meal. Combining video, fisheries data and traditional tagging over several years will help build accurate models to understand the impacts of changing ocean conditions on this depleted population. While analysis is ongoing, the results of this study can be used to inform and refine bioenergetics models of the needed food for this depleted population, as well as validate estimates of northern fur seal consumption of walleye pollock, a commercially important fish stock.

For the fifth year, researchers used saildrones to collect these measurements to venture further and tackle bigger questions on how this cutting-edge technology can be used for innovative science and perhaps provide critical observations in areas that have been difficult to access using traditional methods.

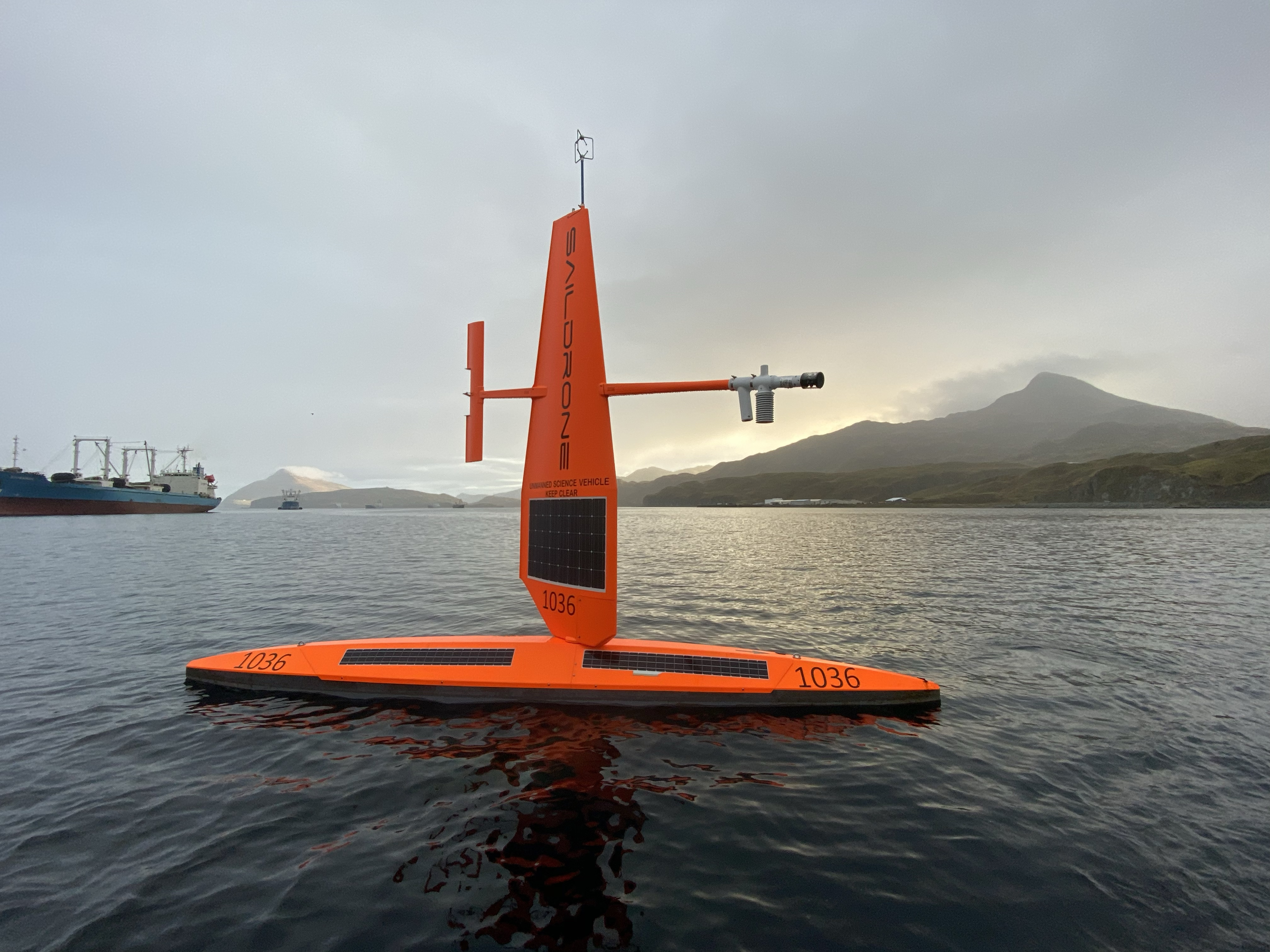

Saildrones are powered by wind and the sun's rays and until this year, have traveled about 45,000 nautical miles on NOAA Arctic missions since 2015. Each year, Saildrone Inc. refines these vehicles for data collection with NOAA scientists and engineers who have helped integrate over 15 sensors into the drone.

Mini Wrap-up

No. of saildrone: 6 (4 NOAA PMEL & ARCTIC, 2 NOAA NOPP/NASA)

Total Mission Days: 147

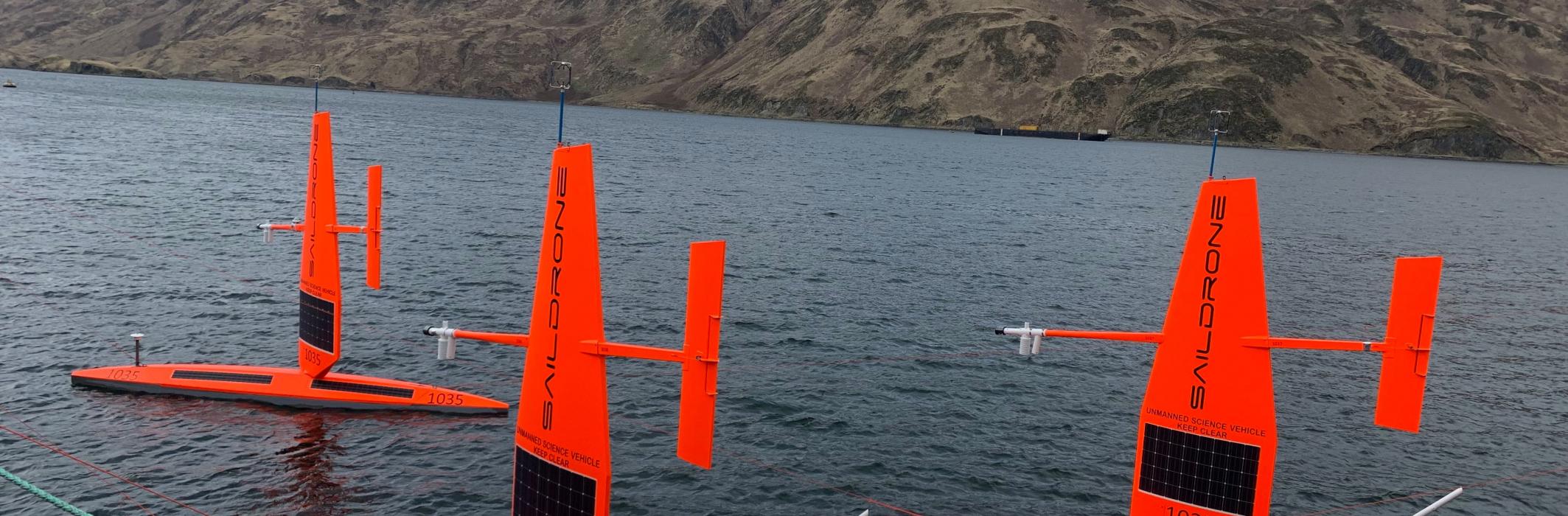

Launched: Dutch Harbor, AK (16 May, 2019, 6 drones)

Recovered: Utqiaġvik, AK (4 October, 2019, 1 drone) & Dutch Harbor, AK (13 October, 5 drones)

Furthest northern latitude reached: 75.49 N

Total distance traveled: over 36,000 nautical miles

18 October - Successful Recovery of Five Saildrone in Dutch Harbor, AK

Today, the remainder of the Arctic vehicles were safely recovered in Dutch Harbor, AK and packed up in containers ready for shipment back to Alameda, CA where Saildrone Inc. is based.

October - Successful Recovery of One Saildrone in Utqiagvik, AK

One of the vehicles has been on quite the journey this mission, and we were not sure it would make it safely to land. With persistence and a skilled team, the drone that was stuck in the ice and lost use of it's rudder tab back in August, was recovered safely this week from Utqiagvik, AK. There was still no snow or ice in Barrow, which was very lucky for the recovery, however, a visible reminder that there is rapid arctic change. The recovery team reported that that the locals said that "is is normally starting to ice up and covered in snow by now" and that it was the "warmest fall anyone can remember".

1 September - Drone View: Early morning

26 August - Pushing the Limits

One of the vehicles from this years mission, ended up scrunched in a patch of drifting ice with strong winds. Unfortunately, it soon after, lost control and it appears the use of the rudder tab has ceased.

17 June - Drone View: Strait (in)to the Ice

16 June - Strait (in)to the Ice

We did it! We reached the ice! It wasn't quite in the plan (yet), but we accidentally got stuck in an ice field on our way to rendezvous with a profiling float. The ice was broken and slushy, so the drone was able to return to open water. It is tricky navigating ice when you are relying on satellites and ocean properties. Our science team, each day, are creatively working to best use the assets available. We considered there might be a chance the really cold ocean temperature (below zero celsius) or fresher salinity near the ice, would help indicate when we were entering the ice field, an hour or so ahead. And unlike we thought (or were hoping), there was no warning evident in the measurements we collected. Both the temperature and salinity decreased, only as we got into the ice field.

Did you know that sea ice is simply frozen ocean water? It forms, grows, and melts in the ocean. And because ocean water is saltier than lakes and rivers, the process by which sea ice forms is much slower. [Learn more about sea ice from the National Snow & Ice Data Center here: https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/seaice/index.html]

More posts to come. Stay tuned!

14 June - Drone View: A beautiful day to cross Bering Strait

The last of the five drones made it's way through Bering Strait yesterday. It was a beautiful, sunny and clear day. Fairway Rock is located about 10 miles southeast of Little Diomede Island at the western end of the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. The rock is 534 feet high, square headed, and steep sided. The rock was first mapped by Captain James Cook in 1778 and named in 1826 by Captain Frederick William Beechey, of the Royal Navy, because it is an important navigation guide to the preferred eastern channel through the Bering Strait. The 58 mile wide Bering Strait links the Bering and Chukchi Seas, forming the Pacific gateway to the Arctic Ocean. The boundary between the United States and Russia extends through this strait, splitting two small islands, Little Diomede (U.S.) and Big Diomede (Russia) only 2.5 miles apart at their closest point. The vehicles stayed well away from land on both sides of the strait, but both were able to see the distant outline of Little Diomede and Fairway Rock on the horizon. This will likely be the last land these drones see for some time.

28 May 2019 - In Pursuit of the Ice Edge

Scientists are sailing drones to the ice edge in the US Arctic Ocean following fur seals and exploring the areas near-ice.

On 16 May, six sailing drones loaded with scientific instruments and cameras launched from a dock in the Alaskan community of Dutch Harbor, gliding past volcanic islands and the iconic fishing fleet, on a northward journey towards the ice edge. Off the coast of Alaska, NOAA and partners are sleuthing ongoing changes to the U.S. Arctic ecosystem food-chain, ice movement, and climate and weather systems. For the fifth year, researchers are using ocean drones to collect these measurements and venturing further and tackling bigger questions on how this cutting-edge technology can be used for innovative science and perhaps provide critical observations in areas that have been difficult to access using traditional methods.

Satellite measurements are less accurate in the Arctic. This is because there are few ground truth observations to compare them too. This is the first year NOAA and NASA scientists will be working together and intentionally planning that the drones survey as close to the Arctic ice edge as possible. Chidong Zhang, oceanographer with NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, is leading the mission to enhance sea ice prediction. "PMEL has pioneered the application of saildrones to study the marine ecosystem in the open water away from sea ice," Zhang said. "This year, we plan to approach the sea ice—as close as we can. The saildrones gather a much richer, high-resolution dataset to supplement foundational data collected by buoys and vessels used to build forecasting models today."

Measurements collected this summer in the Arctic will not only be used to improve NOAA and NASA satellite ocean temperature measurements, they will also be available to global weather agencies for operational use. Chelle Gentemann, an oceanographer with Earth & Space Research, is the principal investigator on an interagency effort (funded by the National Oceanographic Partnership Program ) collaborating with Dr. Zhang for a sub-set of the NOAA missions. "We are helping to ensure that the saildrone observations are used by NOAA, NASA, and the US Navy scientists for weather forecasting and satellite sea surface temperature measurements in the Arctic," says Gentemann. "The near-ice edge observations taken this summer will be especially important for understanding the accuracy of these satellite observations." After these near-ice edge observations, two of the sailing drones will split off from the group to examine how small-scale variability in the ocean can imprint itself on larger-scale weather patterns.

While most of the saildrones will be pursuing the ice edge for the duration of the three-month exploration, two other concurrent projects will also tackle some big questions on how the Arctic ocean is changing and what that means for not only humans but the fish and marine mammals that inhabit the region.

Jessica Cross, oceanographer with NOAA's PMEL, is continuing her use of the sailing drones to study how the region is absorbing carbon dioxide and our understanding of ocean acidification in these critical ecosystem areas. "I am extremely excited to be deploying carbon sensing equipment in the far north for the third year in a row," said Cross, who is working with NOAA's Arctic Research and Ocean Acidification Programs in support of the Distributed Biological Observatory. "This is an amazing partnership because the DBO has such a great time series of ecosystem impacts and a history of close community and indigenous relationships. That helps put our carbon work in a real-world context and ensure that our research has the highest impact that it can."

One drone will be on its own this year in the Bering Sea, home to the largest walleye pollock fishery and the depleted stock of northern fur seal. Critical information is still lacking about the relationship between the fur seals and their prey, which is predominantly walleye pollock. The Pribilof Islands support the largest aggregation of northern fur seals in the US, which breed on St. Paul among other nearby islands. This year, Carey Kuhn, an ecologist with NOAA's Alaska Fisheries Science Center, continues to elucidate the feeding behavior of several female fur seals using traditional at-sea tracking techniques combined with the drone and video cameras to get a seals-eye view during fur seal feeding trips. Multi-year data like this are critical to build accurate models to understand the impacts of changing ocean conditions on this depleted population. "Having this additional year to conduct research gives us the opportunity to examine how annual variability in the fur seals' habitat impacts fur seal foraging," said Kuhn. "And we are thrilled to have the opportunity to be a part of the Arctic Saildrone mission for a third year."

Saildrones are powered by wind and the sun's rays and have traveled about 45,000 nautical miles on NOAA Arctic missions since 2015. Each year, Saildrone Inc. refines these vehicles for data collection with NOAA scientists and engineers who have helped integrate over 15 sensors into the drone.

01 May 2019 - Where We Left Off

On 30 June, 2018 four sailing drones launched from Dutch Harbor, Alaska and crossed into the Chukchi Sea, to measure carbon dioxide and the abundance of Arctic cod in the Arctic Ocean, and safely returned to Dutch Harbor, AK. The two missions gathered measurements to identify ongoing changes to the Arctic ecosystem and how those changes may affect the food-chain as well as large-scale climate and weather systems. In 2019, we will continue sleuthing ongoing changes to the U.S. Arctic ecosystem including the return of a Bering Sea mission to carry-out reconnaissance fisheries surveys and follow northern Fur Seals. Stay tuned for more information, as we plan to launch the platforms again, sometime mid-month.